'The Most Hideous Institution on this Earth' - Chapter 4 of Decoding Chomsky

In the last chapter, I tried to present Chomsky’s arguments in as positive a light as I could manage. But to understand how it came about that Chomsky so accurately hit the mood of the times, we need to recall the way in which, during the Second World War, the United States military brought together computer scientists, psychologists, linguists and manufacturers of armaments and other equipment, pressing them to integrate human operators into their projects and designs. We need to understand why the challenges they faced prompted them to reject – or at least to question – behaviourist stimulus–response psychology long before anyone had heard of Noam Chomsky.

Too often, Chomsky is depicted by his supporters as the genius who overthrew behaviourism single-handedly. That narrative overlooks how the ground had already been prepared by influential sections of the US military and industrial establishment which, as I will now attempt to show, had been bridling at the narrowness of behaviourist dogma for their own reasons since the early years of the war. Well before Chomsky intervened, glimpses of a new, mind-focused cognitive science were appearing within the Pentagon-funded think tanks and laboratories, although in most cases these were still bound up with lingering behaviourist assumptions. Behaviourism’s fundamental claim had been that mental states could not be studied; only behaviour can be known. But the development of computers changed all that. The revolutionary new ‘computational theory of mind’ – keystone of the ‘cognitive revolution’ – was based on the idea that the human brain is a digital computer or ‘information-processing device’. Mental states, correspondingly, could be viewed as the variable discrete states of such a machine. But as ‘mind’ was being reinstated during and immediately following the Second World War, the secrecy surrounding developments in the think tanks of the US military left the world at large mostly unaware.

The Pentagon’s scientists had little incentive to air their military agendas in public and had been keeping most of their important discoveries under wraps. While Chomsky appeared to be slaying the behaviourist monster single-handedly, the truth is that wartime requirements of command and control had long been tipping the scales his way. It was Corporate America’s urgent need for a mind-centred psychology – not Chomsky’s later eloquence in championing it – that at the deepest level spelt doom for behaviourism and guaranteed the cognitive revolution’s rapid and stunning success. Chomsky’s actual role can best be appreciated by taking a step back from immediate events. How might the situation have looked without him? At a formal ceremony on 15 February 1946, just before pressing a button that set the latest digital computer (ENIAC) to work on a new set of hydrogen-bomb equations, Major General Gladeon Barnes spoke of ‘man’s endless search for scientific truth’.[1] When people heard a beribboned general mouthing such phrases, there was a danger that they would respond with cynicism. For well over a decade, news of intriguing developments in cognitive science had been seeping into the public realm, but only in the vaguest terms and mostly in the words of uninspiring military figures such as Major General Barnes. How much better to find a genuinely idealistic spokesperson who could step in and do the necessary public relations job, speaking with real passion and conviction. Clearly, any such standard-bearer would need to be a civilian, with absolutely no military connections.

In all these respects, Noam Chomsky turned out to be the ideal candidate. Far from sharing his colleagues’ excitement about the prospects of nuclear weaponry, his instincts had always recoiled from the very idea: I remember on the day of the Hiroshima bombing . . . I remember that I literally couldn’t talk to anybody. There was nobody. I just walked off by myself. I was at a summer camp at the time, and I walked off into the woods and stayed alone for a couple of hours when I heard about it. I could never talk to anyone about it and never understood anyone’s reaction. I felt completely isolated. [2]

So it was in many ways a cruel irony that this genuinely idealistic teenager should find himself, years later, in an electronics laboratory whose publicly stated mission was to develop command-and-control systems for nuclear and other military purposes.

In the early 1950s, Chomsky still had no expectation of an academic career and, as he says, ‘was not particularly interested in one’.[3] Perhaps his strongest motive for getting academically qualified in the first place was to avoid being drafted to fight in the Korean War.[4] He did manage to get a fellowship at Harvard, but had no expectation of a job there. As he later explained, ‘Jewish intellectuals couldn’t get jobs’ in many universities and, at Harvard, ‘you could cut the anti-Semitism with a knife’.[5]

One reason he ended up at MIT was because, being Jewish, he could not get a job anywhere else. ‘I had no thought of going into the academic world because there was nowhere to go’, he recalls. ‘But Jakobson suggested I talk to Jerry Wiesner, and so I did.’[6] With engaging modesty he elaborates: ‘When I got my degree, PhD, which was total fraud incidentally, I hadn’t done any work or anything else . . . I had no professional qualifications at all and that’s why I went to MIT because they didn’t care . . . because they were getting a ton of Pentagon money.’[7]

Even after he began working at MIT, Chomsky was not necessarily committed to the job and still had in mind that he might leave America to live on a left-wing kibbutz with his partner, Carol. But the difficulties of life in Israel after only a few weeks seem to have persuaded the young couple to remain in the United States.[8]

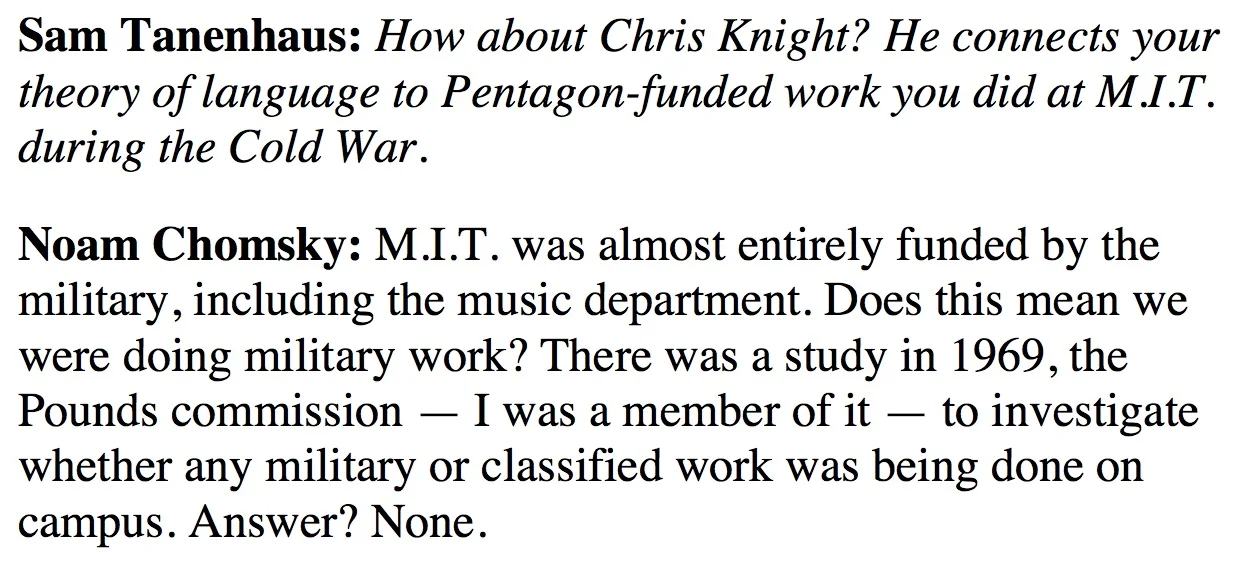

Having decided to stay on at MIT, it wasn’t long before Chomsky found himself being honoured, promoted, financed and hoisted aloft by the very establishment whose foreign policy crimes he so passionately opposed. It was a favourable wind that would prevail for the next 60 years. Given the paradox that an anti-militarist activist was working in the world’s foremost military research centre, there were going to be challenges in keeping both parties on board. But Chomsky’s relaxed and informal demeanour and his appealing stance as a military outsider undoubtedly helped. Watching him deliver a lecture or seeing him on television, it was often difficult for an onlooker to keep the other side of his life in mind. His political passion was directed against the US military. But, as he said about MIT as it was in 1969: ‘[The university] was about 90 percent Pentagon funded at that time. And I personally was right in the middle of it. I was in a military lab.’[9] Chomsky may have been an anarchist, but he was also in the belly of the beast.

The largest of America’s wartime university research programmes, MIT’s Radiation Laboratory was the renowned institution where radar (invented in Britain, but for security reasons hastily shipped over to the United States) had been successfully developed. Armies of academics from across America had been coordinated via this laboratory to work for industrial and military research groups. Industrial scientists collaborated with their university colleagues, and generals were frequent visitors. In this way, the war had brought about the most radical centralization and reorganization of science and engineering ever accomplished in the United States.[10] It would be hard to exaggerate the long-term ideological impact of MIT’s Radiation Laboratory as a vast interdisciplinary effort restructuring American scientific research, solidifying the trend to science-based industry – and, in the process, introducing unprecedented levels of government funding and military direction of intellectual life.

Chomsky was the right man in the right place at exactly the right time. MIT emerged from the Second World War with a staff twice as large as the pre-war figure, a budget four times as large, and a research budget magnified tenfold – 85 per cent of it from the military services and the Atomic Energy Commission.[11] Eisenhower famously named this sprawling corporate monster the ‘military-industrial complex’, but – as historian Paul Edwards notes – the nexus of institutions is perhaps better captured by the concept of an ‘iron triangle’ of reciprocally self-perpetuating academic, industrial and military collaboration.[12] If you had military funding, as Chomsky notably did, that gave you not only plentiful money, but also enviable academic status, from which you could hope to attract still more financial and other institutional support.

But why did this military institutional and funding context lead Chomsky to what is most characteristic about his philosophical outlook – the extreme way in which he splits what is pure and ideal from what is messy and real? Later, it will become clear how such bifurcation was intrinsic to the computational theory of mind, which pictured information as independent of the material which carried it. But my suggestion is that, in Chomsky’s case, there was more to it than that. He found in the mind/ body split a means of escape – escape from the potentially painful moral implications of the work he was doing.

Chomsky himself has written of his need to be able to look himself in the mirror each morning ‘without too much shame’.[13] Employed to conduct research on a Pentagon-funded device – a ‘language machine’ – he needed to keep his conscience clear. There was no problem here, he would sometimes argue, since his own institution embodied ‘libertarian values’:

It’s true that MIT is a major institution of war research. But it’s also true that it embodies very important libertarian values . . . Now these things coexist. It’s not that simple, it’s not just all bad or all good. And it’s the particular balance in which they coexist that makes an institute that produces weapons of war willing to tolerate, in fact, in many ways even encourage, a person who is involved in civil disobedience against the war.[14]

But Chomsky may not have been entirely happy with this line of thought. True, MIT did espouse ‘libertarian values’ – most universities do. But in the United States, ‘libertarian’ can mean almost anything, being frequently associated with the far right. Beyond that, Chomsky could hardly describe MIT’s primary sponsor, the Pentagon – ‘the most hideous institution on this earth’[15] – as libertarian. The weapons research conducted on campuses like his own was explicitly designed, according to him, ‘to harm people, to destroy and murder and control’. ‘As far as I can see,’ Chomsky continued, ‘it’s elementary that that kind of work simply should not be done.’[16]

All this shows just how strong were Chomsky’s misgivings, even while he was doing the intellectual work which he loved. In mitigation, he could argue that it was scarcely possible to conduct scientific research in an American university without military funding:

Ever since the Second World War, the Defense Department has been a main channel for the support of the universities, because Congress and society as a whole have been unwilling to provide adequate public funds. Luckily, Congress doesn’t look too closely at the Defense Department budget, and the Defense Department, which is a vast and complex organization, doesn’t look too closely at the projects it supports – its right hand doesn’t know what its left hand is doing. Until 1969, more than half the MIT budget came from the Defense Department, but this funding at MIT is a bookkeeping trick. Although I’m a full-time teacher, MIT paid only thirty to fifty percent of my salary. The rest came from other sources – most of it from the Defense Department. But I got the money through MIT.[17]

Despite all this, Chomsky’s conscience remained active. Looking back on his early career, he once explained that the electronics laboratory to which he had been recruited was one of several to have been misleadingly named:

They should have an honest name for it. It shouldn’t be called Political Science or Electronics or something like that. It should be called Death Technology or Theory of Oppression or something of that sort, in the interests of truth-in-packaging. Then people would know what it is; it would be impossible to hide. In fact, every effort should be made to make it difficult to hide the political and moral character of the work that’s done.[18]

Changing the name in this way, continued Chomsky, might provoke sufficient outrage to disrupt or even halt the work:

I would think in those circumstances it would tend to arouse the strongest possible opposition and the maximal disruptive effect. And if we don’t want the work to be done, what we want is disruption: maybe the disruption will be the contempt of one’s fellows.[19]

As we shall see, Chomsky had no appetite for the contempt of his fellows, whether these were university administrators or radical students. Chomsky is right in saying that his own work at MIT was in one sense nothing special: military sponsorship was (and remains) essential to many areas of Western scientific research. But, whether in linguistics or any other field, the problems accorded priority do tend to follow the funding. As a laser scientist at Stanford University explained: ‘Nobody likes [military] support less than we do . . .The problem is, when the military supports everything, they’re the people who come around with the problems and so you think about those problems.’[20] At MIT in the 1960s, well-funded research laboratories were working on helicopter stabilization, on radar for tracking bomb targets and on various counterinsurgency techniques – all useful technologies for the ongoing war in Vietnam.[21] At the same time, as Chomsky explained in an interview in 1977, ‘a good deal of [nuclear] missile guidance technology was developed right on the MIT campus’.[22]

By late 1968, the student unrest of the period had spread to MIT, largely in opposition to the Vietnam War, but specifically in opposition to MIT’s role in the whole US war machine. Chomsky’s university soon became, in his own words, ‘one of the most militant campuses in the country’.[23] A confrontation erupted between the administration and a radicalized student body demanding the removal of all defence-related research from the campus. Late in 1969, at the height of the protests, activists in the ‘November Action Committee’ explained:

MIT isn’t a center for scientific and social research to serve humanity. It’s a part of the US war machine. Into MIT flow over $100 million a year in Pentagon research and development funds, making it the tenth largest Defense Department R&D contractor in the country. MIT’s purpose is to provide research, consulting services and trained personnel for the US government and the major corporations – research, services, and personnel which enable them to maintain their control over the people of the world.[24]

These activists went on to explain that their recent action was ‘directed against MIT as an institution, against its central purpose.’[25] Clearly, these students were aiming at an all-out confrontation. But despite this, Chomsky’s recollection was different. According to him, ‘Nobody wanted the confrontation on either side. The dynamics of that kind of thing are pretty obvious. So how do you get out of a confrontation? You set up a committee. So the committee was set up to investigate it and I was kind of implored by the Dean and the students to be on it.’[26]

The dean, or more accurately the president of MIT, was Howard Johnson, who made clear that he needed Chomsky on his committee ‘to satisfy the radicals’.[27] This had the effect, it seems, of persuading at least one of these radicals – Jon Kabat – to drop his former resistance and agree to join as well.[28] The subsequent lengthy deliberations, of course, helped Howard Johnson take ‘the steam out of the lab situation’.[29] As one student told a journalist at the time, ‘[Johnson] is smart. He’ll co-opt you before you know what’s happening.’[30] Between Chomsky and Johnson, astute politicking won the day.

Five months later, the committee produced a final report, to which Chomsky added a dissenting appendix. Chomsky’s delicate compromise position was that ‘we should not sever the connection with the special laboratories but should, rather, attempt to assist them in directing their efforts to “socially useful technology” ’. He continued:

In my opinion, the special laboratories should not be involved in any work that contributes to offensive military action. They should not be involved in any form of counterinsurgency operations, whether in the hard or soft sciences. They should not contribute to unilateral escalation of the arms race. They should not be involved in the actual development of weapons systems. They should be restricted to research on systems of a purely defensive and deterrent character.[31]

Years later, when Chomsky recalled these events, he put a slight gloss on them:

The students and I submitted a dissident report disagreeing with the majority. The way it broke down was that the right-wing faculty wanted to keep the labs, the liberal faculty wanted to break the relations (at least formally), and the radical students and I wanted to keep the labs on campus, on the principle that what is going to be going on anyway ought to be open and above board, so that people would know what is happening and act accordingly.[32]

But Chomsky’s suggestion that he and the radical students formed a unified bloc does less than justice to the complexities of the situation. The key student activists of the time have different memories.

One of those activists was Stephen Shalom, who complains that Chomsky’s recollection (as recorded by Robert Barsky) ‘obscures the fact that most radical students, as well as many liberal students, wanted first and foremost to stop the war research’.[33] A second activist, George Katsiaficas, who actually sat on the MIT committee along with Chomsky, simply recommended ‘the immediate curtailment of weapons research’.[34] A third dissenting activist was MIT’s student president at the time, Michael Albert, for whom Chomsky’s compromise, however well intentioned, threatened to take the steam out of the whole campaign: ‘Given attitudes at MIT, we could successfully organize around closing down research . . . We could not develop support for preserving war research with modest amendments.’[35] The three most prominent student activists – Albert, Katsiaficas and Kabat – all described the final report as a ‘smokescreen’.[36] Considering all this, it is not surprising that Chomsky himself says that he had ‘considerable conflict’ with radical students in this period.[37]

Adding to this picture of Chomsky on the horns of a dilemma, some MIT faculty members remember him as not particularly radical in this period. We are told that Chomsky was in fact one of the signatories when the initial, May 1969, version of the MIT committee report recommended keeping both the military labs functioning – although he did later change his mind.[38]

The complexities of these events become still more apparent when other perspectives are recalled. Asked about the atmosphere at MIT in the late 1960s, one professor recalls: ‘Things were brewing; the radical student vibrations were going on. They were in a siege mentality. All of the people in the upper administration carried walkie-talkies with them.’ He then offers his own explanation as to how and why the students were defeated: All radical revolutionary movements of any kind, if you read history, make the same mistake . . . They have to decide whether to move closer to the establishment – or to become more radical. And they always make the same mistake. They become more radical, and the establishment destroys them.

See, when we were standing in the president’s office trying to protect the president’s office from the radical students, I’d look up and I’d be standing right beside Noam Chomsky.

The interviewer intervenes at this point, remarking that Chomsky was ‘perceived as quite a radical himself ’. The professor replies: ‘Yes. But not if you’re going to mess around with our institution.’ He continues: ‘And the time that the students interrupted a class? Oh, my God. The faculty came down with a giant iron fist. It was a wild time. But we got through it; we got through it.’[39]

By early 1970, Michael Albert had been expelled from MIT, provoking other students to occupy and damage the president’s office. Having begun the process of expelling more students and securing the imprisonment of two of them for the alleged crime of ‘disruption of classes’,[40] the grateful professors then organized a surprise party for Howard Johnson, during which they cheered their long-suffering president and presented him with an engraved clock.[41] Somehow, Chomsky managed to sign a letter calling for an amnesty for the protestors, while also turning up at this celebratory party, at least according to Johnson’s recollection.[42]

Whatever the accuracy of these scattered reminiscences, Chomsky has stated candidly that he considered the student rebels of the period ‘largely misguided’ and their actions, in some cases, ‘indefensible’.[43] Rather than urging the students forward at this time, he advised postponement and delay on the basis that ‘The search for confrontations is a suicidal policy.’[44] But while Chomsky was in two minds about disrupting university campuses, he showed rare courage, intransigence and extraordinary confrontational spirit on the wider political stage. In the spring of 1970, at the height of the Vietnam War, he accepted an invitation from the North Vietnamese government to visit Hanoi, giving a seven-hour lecture on linguistics to an enthusiastic audience at the University of Hanoi. During the trip he also spoke to Premier Pham Van Dong, to the editor of the Communist Party newspaper, and to various intellectuals and peasants, receiving a cordial welcome everywhere as a ‘progressive American’.[45]

Chomsky’s was merely an extreme case of a more general predicament for liberal academics in the period. But the situation at MIT was particularly strained. President Howard Johnson ended up imposing an injunction and welcoming in riot police to protect what he termed a ‘free and open university’. In fact, Johnson was protecting the right of workers at the university to work on guidance systems for nuclear missiles.[46] Johnson’s subsequent replacement, Jerome Wiesner, then ended up doing his best to get more anti-war students sentenced to prison while, at the same time, insisting that he, like them, was opposed to the war in Vietnam. In fact, Wiesner continued to oversee a huge military research programme at MIT, naturally justifying this on grounds of ‘academic freedom’.[47]

The strain on Chomsky was clearly showing as early as March 1967, when he admitted in a private letter (immediately published in the New York Review of Books) that ‘I have given a good bit of thought to . . . resigning from MIT, which is, more than any other university associated with the activities of the department of “defense” . . . As to MIT, I think that its involvement in the war effort is tragic and indefensible. One should, I feel, resist this subversion of the university in every possible way.’[48] Then, only a few weeks later, he had second thoughts about such blatant criticism of his employer. In a new letter, he chose to ‘reformulate’ his earlier statement against MIT: ‘This statement is unfair, and needs clarification. As far as I know, MIT as an institution has no involvement in the war effort. Individuals at MIT, as elsewhere, have a direct involvement, and that is what I had in mind.’[49] Did something happen in between these two letters – some pressure from above which made him fear for his job?

Chomsky was genuinely grateful to the student activists of the 1960s for transforming the atmosphere at MIT and he acknowledged that they suffered things ‘that should not have happened’.[50] But he always defended MIT as an institution, describing Howard Johnson as ‘an honest, honorable man’.[51] In one interview in 1996 Chomsky claimed that:

MIT had quite a good record on protecting academic freedom. I’m sure that they were under pressure, maybe not from the government, but certainly from alumni, I would imagine. I was very visible at the time in organizing protests and resistance. You know the record. It was very visible and pretty outspoken and far out. But we had no problems from them, nor did anyone, as far as I know, draft resisters, etc.[52]

In another interview, he said:

I have been at universities around the world and this is the freest and the most honest and has the best relations between faculty and students than at any other university I have seen. That may be because MIT is a science-based university. Scientists are different. They tend to work together, and there is much less hierarchy.

He then went on to claim that MIT has ‘quite a good record on civil liberties. That was shown to be particularly true during the sixties.’[53]

These remarkable statements make more sense when we appreciate that Chomsky’s position on academic freedom uncannily resembled the MIT management line on these issues. You can research what you like – provided you don’t actually do anything about it. That line was succinctly expressed by Howard Johnson in October 1969 when he was desperately trying to prevent students from disrupting MIT’s military labs: ‘[The university] is a refuge from the censor, where any individual can pursue truth as he sees it, without any interference.’[54]

It is only against this background that we can properly understand what happened when Chomsky later took up a position which laid him open to charges of anti-Semitism. Over the years, Chomsky’s right-wing detractors have made much of his defence of holocaust denier Robert Faurisson. In 1979, Chomsky famously signed a petition stating: ‘We strongly support Professor Faurisson’s just right of academic freedom and we demand that university and government officials do everything possible to ensure his safety and the free exercise of his legal rights.’[55] Whatever we may think of the wisdom of Chomsky’s intervention, his detractors ought to acknowledge that his position did not imply any sympathy towards holocaust denial. It was simply a logical extension of a principle common to all Western universities – one which his management at MIT felt obliged to uphold with special tenacity in view of what its own researchers were doing.

To take an example, one of MIT’s researchers was the economist Walt Rostow who had produced influential theories on how to counter the ‘disease’ of communism in the Third World. Rostow had since left MIT to work as an adviser to the US government, where he had become one of the major architects of the Vietnam War. In fact, Rostow had advocated escalating that war more vigorously than almost anyone else in the US government, even urging it to risk a nuclear stand-off with Russia. With Nixon’s election victory in 1968, however, he lost his government job and was looking to return to MIT.[56] In the event, MIT decided not to offer Rostow a job, probably because it already faced enough campus unrest over the Vietnam War.[57] It was at this point that Chomsky took it upon himself to demand that his university stick to its own liberal principles by letting Rostow return. Let Chomsky himself explain:

In fact, as a spokesman for the Rosa Luxemburg collective, I went to see the President of MIT in 1969 to inform him that we intended to protest publicly if there turned out to be any truth to the rumours then circulating that Walt Rostow (who we regarded as a war criminal) was being denied a position at MIT on political grounds.[58] In short, at a time of mounting anti-war unrest, Chomsky seriously proposed that he could lead MIT’s most radical students in a campaign to defend the right of someone he regarded as a ‘war criminal’ to rejoin the university community.

When Rostow visited the campus for just one day that year, the improbability of this scenario became crystal clear. Although some anti-war students were reluctant to prevent Rostow from speaking, others angrily disrupted his talk. One complained, ‘He has a lot of blood on his hands’, while Michael Albert argued that ‘nobody has the right to listen to him’.[59] George Katsiaficas did support Rostow’s right to free speech,[60] but remains to this day uncompromisingly critical of MIT’s abuse of this ideal:

Academic freedom when it was originally developed in Europe was to protect the rights of dissident people who disagreed with the church, who disagreed with the government, to speak up without sanctions. It was never intended to protect the rights of war makers to make weapons of mass destruction or to harm other people. It was always intended for professors and the university community to be a place of free speech in order to have free debate . . . I think Harvard today and MIT and large universities hide behind the veil of academic freedom to mask the fact that they are prostituting universities to big government and to the military.[61]

Michael Albert’s words on MIT are even harsher: ‘War blood ran through MIT’s veins. It flooded the research facilities and seeped even into the classrooms.’ [62] While a student, he described the place as another ‘Dachau’, explaining years later that ‘MIT’s victims burned in the fields of Vietnam’. ‘I’d certainly have lit a match,’ he added, ‘if I thought it would have done any good.’[63] Asked about his expulsion, Albert replied: ‘Well, for me, it didn’t mean much, in the sense that it’s a little like being expelled from a cesspool.’ [64] Despite their contrasting overall verdicts on MIT, Chomsky never fell out with any of these former students, Albert in particular remaining a close colleague to this day.

How do you collude with the military-industrial complex, work for it – and express moral opposition to its objectives at the very same time? I hope I have shown that Chomsky was not alone in experiencing such contradictory pressures. But the truth is that while many liberal academics at MIT felt under similar pressures, Chomsky was torn more than most – and for that reason reflected the contradictions of his institutional situation more than most. On the one hand, he needed to retain the confidence of MIT’s president, keep his job and reassure his colleagues in the Research Laboratory of Electronics that he was a loyal member of their team. On the other, he needed to eliminate the slightest suspicion that his research in that laboratory could possibly be aiding the US military in any practical way.

Many a lesser mind might have given up, concluding that it was impossible to reconcile such flatly opposing demands. Chomsky’s genius was to fathom a way. His solution, fitting nicely with a core tenet of the so-called ‘cognitive revolution’, was to separate knowledge in the head from its social or political use. In his particular case, that meant separating theory from practice in a ruthlessly consistent and far-reaching way.

In his role as a linguist, perhaps the most familiar fact about Chomsky is that he isolates knowledge of language as something separate from its use. What lies quietly in the head differs absolutely and categorically from anything going on in the social or political world. This well-known Chomskyan dichotomy – conventionally the distinction between competence and performance – has traditionally been viewed as a reflection of the linguist’s rationalist philosophy. But my aim here is not merely to give that philosophy a label, but to offer an explanation for it. My conclusion is straightforward. In Chomsky’s hands, a careful reformulation of Descartes’s celebrated distinction between body and soul would free him, as one interviewer put it, ‘to have it both ways’[65] – to get up each morning at ease with his own conscience, while continuing to work in that Pentagon-funded laboratory at MIT.

There is no need to picture Chomsky as double-dealing or politically insincere. I prefer to think that his elimination from linguistics of all things social was a necessary move, given his situation. As a thought-experiment, imagine a social anthropologist recruited to work alongside Chomsky in his MIT laboratory. Chomsky would have suspected that person of collusion with unsavoury pursuits, such as psychological warfare, intelligence gathering and counterinsurgency – rightly, as it turns out.[66] Suspicious of their politics, Chomsky has never shown much sympathy for sociologists or social anthropologists. Only if he could extricate linguistics from its former position as a discipline within anthropology – cutting it off from any possible social meaning or content – would he feel on safe ground. Pursuing this logic to the very end, Chomsky eliminated from linguistics not only real human beings, but – just to be safe – all social life and interaction. Since linguistic communication connects a speaker with a listener, not even communication could be allowed.

If language could be reduced to pure mathematical form – devoid of human significance – its study could be pursued dispassionately, as a physicist might study a snowflake or an astronomer some distant star. As Chomsky himself puts it, the various aspects of the world might then all ‘be studied in the same way, whether we are considering the motion of the planets, fields of force, structural formulas for complex molecules, or computational properties of the language faculty’.[67] In 1955, when Chomsky first got his job at MIT, he set out with that goal in mind; in subsequent years, he has refused to abandon the project. Linguistics, he asserts, should be as formal and free of political contamination as Galilean astronomy, Newtonian physics or Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Chomsky’s ideal of linguistics as pure natural science has always seemed inspirational and liberating. But his activist and academic admirers were not the only people to be pleased. Paradoxically, as I will argue here, the project for a wholly non-political linguistics – cut off in particular from Marxist-inspired social science – suited not only its inventor, but, more significantly, the US military-industrial establishment responsible for the funding and development of science and technology in the immediate post-war years. Critics from the left have always complained that hidden agendas can be far more damaging than those which are public and explicit. It is ‘our belief ’, write John Joseph and Talbot Taylor in their book Ideologies of Language, ‘that any enterprise which claims to be non-ideological and value-neutral, but which in fact remains covertly ideological and value-laden, is the more dangerous for this deceptive subtlety’.[68]

Evidently, Chomsky does not agree: he believes that his linguistic work really is neither ideological nor political at all. When Einstein was working on his theory of relativity, he did not consider himself to be colluding with militaristic ideology or encouraging the production of an atomic bomb. Provided he restricted himself to pure science, he hoped that his conscience in these respects would not burn. Chomsky clearly saw things the same way. If he could separate his science from any possible social or practical application, he could keep his conscience clear – even if it meant bifurcating his own mind into utterly separate spheres.

Notes

1. Edwards 1996, 51.

2. Chomsky 1988h, 14.

3. Chomsky 1988h, 9.

4. Hughes 2006, 86–87.

5. Chomsky 2003; Jaggi 2001.

6. Chomsky 2011c, 44 mins.

7. Chomsky 2013a, 1 hour 31 mins.

8. Barsky 1997, 82–83.

9. White 2000, 445.

10. Edwards 1996, 47.

11. Forman 1987, 156–157; quoted in Edwards 1996, 47.

12. Adams 1982; quoted in Edwards 1996, 47.

13. Chomsky 1988h, 55.

14. Chomsky 1997c, 144.

15. Chomsky 1967b.

16. Chomsky 1988g, 247.

17. Mehta 1974, 152.

18. Chomsky 1988g, 248.

19. Chomsky 1988g, 248.

20. Leslie 1993, 181.

21. Albert 2006, 97–99.

22. Chomsky 1988g, 247.

23. Chomsky 2015, 43–50 mins.

24. Wallerstein and Starr 1972, 240–241.

25. ‘Why smash MIT?’ in Wallerstein and Starr 1972, 240–241.

26. Chomsky 2015.

27. Chomsky; quoted in Mehta 1974, 153.

28. The Tech, 29 April 1969, 2 May 1969. It is noteworthy that Jon Kabat went on to develop mindfulness meditation techniques which are now used not only by health services but also by the US military. Kabat-Zinn 2014, 556–559.

29. Johnson 2001, 174, 191.

30. New York Times Magazine, 18 May 1969.

31. Chomsky 1969, 37–38.

32. Letter to Barsky dated March 1995; Barsky 1997, 140.

33. Shalom 1997.

34. Katsiaficas 1969, 92.

35. Albert 2006, 98.

36. The Tech, 21 November 1969.

37. Barsky 1997, 122.

38. Skolnikoff 2011, 1 hour 40 mins. This appears to be confirmed by Nelkin 1972, 81. See also Chomsky 1969, 17, 31.

39. Segel 2009, 206–207.

40. The Tech, 22 May 1970. The two jailed students were George Katsiaficas and Peter Bohmer. Another, Stephen Krasner, was later sentenced to a year in prison for constructing the metal ram used to break into Johnson’s office. George Katsiaficas’s mother was also imprisoned for contempt of court. In all, seven students were expelled from MIT, although three were later readmitted. The Tech, 5 October and 14 December 1971; Johnson 2001, 201.

41. Segel 2009, 216; Isadore Singer video interview, MIT 150 Infinite History Project, available at http://mit150.mit.edu/infinite-history/isadore-singer.

42. The Tech, 16 January 1970; Johnson 2001, 202–203.

43. Barsky 1997b, 122; Chomsky 1971b. Chomsky also said that ‘the student movement has focused too much on preventing people from doing this or that, and not enough on creating alternatives. So while I share a lot the indignation and outrage of the kids, I think they’re misled.’ New York Times,

27 October 1968.

44. Chomsky 1971b.

45. The Tech, 5 May 1970.

46. Technology Review, 72 (December 1969), 96.

47. The Tech, 25 and 28 April 1972. In 1972, three students were sentenced to 30 days’ imprisonment for staging a 21-hour occupation of MIT’s military officer training department; The Tech, 4 August 1972. This punishment was clearly acceptable to MIT, but when Stephen Krasner was sentenced to a whole year in prison, Jerome Wiesner did make a failed attempt to prevent such a harsh punishment; Wiesner 2003, 532.

48. Chomsky 1967d.

49. Chomsky 1967e.

50. Chomsky and Otero 2003, 311.

51. Time, 21 November 1969, 68 and 15 March 1971, 43.

52. Chomsky 1996a, 137.

53. Chomsky interviewed in Chepesiuk 1995, 145.

54. Technology Review, 72 (October 1969), 93.

55. Chomsky 1980c.

56. Milne 2008, 7, 60, 71, 93–95, 174–175, 255–257.

57. Johnson 2001, 189–190; Wiesner 2003, 582.

58. Barsky 1997, 140–141.

59. The Tech, 11 April 1969.

60. Personal communication to the author, 19 May 2016.

61. Eun-jung 2015, 78.

62. Albert 2006, 99.

63. Albert 2006, 9. Interviewed in 1975 (The Tech, 95(3), 9–10), Albert had plenty to say about the distorting effect of MIT on the psychology of even the most morally sensitive researcher: 'I still think of MIT the same way I did when I was there. It seems to me that it’s a masquerade as an institution of higher learning and objective science. That’s a byproduct. What it really is is a place where scholars who are really mandarins get together and promulgate a lot of ideas and theories which uphold the status quo and which aid people who are trying to further American interests. That’s on the intellectual side. On the technological side, it’s a place which . . . creates a breed of scientists who don’t question the reasons why they’re doing things but just do them. MIT creates people who are willing to do scientific research as if it’s value-free, as if it isn’t plugging into a system that’s very value-laden. Every so often . . . it gives somebody a good education who then becomes a critical activist. I think it’s a shithole. If you were trying to create somebody who was going to do scientific work without considering the value implications, you’d want someone who in fact had partially lost touch with his own feelings and with the reality of people around him. MIT does exactly that . . . I just think that’s barbaric. You can try to take advantage of it, but it’s a very risky proposition. It can warp you just as much as you get some good out of it. I don’t even know with respect to myself the extent to which it or I won.'

64. Albert 2007; Albert 2006, 107. MIT tried hard to make Albert’s expulsion more damaging for him by calling the Draft Board and ‘urging reclassification’ to get him sent to Vietnam.

65. Chomsky 1988g, 247.

66. Price 2011.

67. Chomsky 1996b, 31.

68. Joseph and Taylor, 1990, 2.

Bibliography

Achbar, M. 1994. Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the media. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

Adams, G. 1982. The Politics of Defense Contracting: The iron triangle. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Albert, M. 2006. Remembering Tomorrow: From the politics of opposition to what we are for. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Albert, M. 2007. ‘From SDS to life after capitalism’, Michael Albert interview, 17 April.

Alcorta, C.S. and R. Sosis. 2005. ‘Ritual, emotion, and sacred symbols: The evolution of religion as an adaptive complex’, Human Nature, 16(4): 323–359.

Atran, S. 2002. In Gods We Trust: The evolutionary landscape of religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baker, G.P. and P.M.S. Hacker. 1984. Language, Sense and Nonsense. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barsky, R.F. 1997. Noam Chomsky: A life of dissent. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Barsky, R.F. 2007. The Chomsky Effect: A radical works beyond the ivory tower. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Berwick, R.C. and N. Chomsky. 2016. Why Only Us: Language and evolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Botha, R. 1989. Challenging Chomsky: The generative garden game. London: Blackwell.

Cartlidge, E. 2014. ‘Faith and science’, Tablet, 1 February.

Chepesiuk, R. 1995. Sixties Radicals, Then and Now: Candid conversations with those who shaped the era. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Chomsky, N. 1967b. ‘On resistance’, New York Review of Books, 7 December.

Chomsky, N. 1967d. ‘Letter’, New York Review of Books, 23 March.

Chomsky, N. 1967e. ‘Letter’, New York Review of Books, 20 April.

Chomsky, N. 1969. ‘Statement by Noam A. Chomsky to the MIT Review Panel on Special Laboratories’, MIT Libraries Retrospective Collection.

Chomsky, N. 1971b. ‘In defence of the student movement’, available at: https://chomsky.info/1971_03/.

Chomsky, N. 1980a. Rules and Representations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chomsky, N. 1980c. ‘Some elementary comments on the rights of freedom of expression’, available at: https://chomsky.info/19801011.

Chomsky, N. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its nature, origin, and use. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Chomsky, N. 1988a. Language and Problems of Knowledge: The Managua lectures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. 1988e. ‘Address given at the Community Church of Boston, December 9 1984’, reprinted as ‘Afghanistan and South Vietnam’, in J. Peck (ed.), The Chomsky Reader. London: Serpent’s Tail, pp. 223–226.

Chomsky, N. 1988f [1968]. ‘The intellectual as prophet’, in C.P. Otero (ed.), Noam Chomsky: Language and politics. Montreal: Black Rose, pp. 85–99.

Chomsky, N. 1988g [1977]. ‘Language theory and the theory of justice’, in C.P. Otero (ed.), Noam Chomsky: Language and politics. Montreal: Black Rose, pp. 233–250.

Chomsky, N. 1988h. ‘Interview’, in J. Peck (ed.), The Chomsky Reader. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Chomsky, N. 1988j [1986]. ‘Political discourse and the propaganda system’, in C.P. Otero (ed.), Noam Chomsky: Language and politics. Montreal: Black Rose, pp. 662–697.

Chomsky: Language and politics. Montreal: Black Rose, pp. 662–697.

Chomsky, N. 1988k. ‘The cognitive revolution II’, in C.P. Otero (ed.), Noam Chomsky: Language and politics. Montreal: Black Rose, pp. 744–759.

Chomsky, N. 1989. ‘Noam Chomsky: An interview’, Radical Philosophy, 53.

Chomsky, N. 1991a. ‘Linguistics and adjacent fields: a personal view’, in A. Kasher (ed.), The Chomskyan Turn. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chomsky, N. 1992. What Uncle Sam Really Wants. Tucson, AZ: Odonian Press.

Cogswell, D. 1996. Chomsky for Beginners. London and New York: Writers and Readers.

Chomsky, N. 1996a. Class Warfare: Interviews with David Barsamian. London: Pluto Press.

Chomsky, N. 1996b. Powers and Prospects. Reflections on human nature and the social order. London: Pluto Press.

Chomsky, N. 1997c. ‘Noam Chomsky and Michel Foucault. Human Nature: Justice versus power’, in A.I. Davidson (ed.), Foucault and his Interlocutors. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press.

Chomsky, N. 1998a. The Common Good. Chicago: Common Courage Press.

Chomsky, N. 1988g [1977]. ‘Language theory and the theory of justice’, in C.P. Otero (ed.), Noam

Chomsky, N. 2000b. New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. 2003. ‘Anti-Semitism, Zionism, and the Palestinians’, Variant, 16 (Winter).

Chomsky, N. 2006a. Language and Mind, third edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. 2007a. ‘Approaching UG from below’, in U. Sauerland and H.M. Gartner (eds), Interfaces + Recursion = Language? Berlin: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. 2007b. ‘Of minds and language’, Biolinguistics, 1: 9–27.

Chomsky, N. 2011c. Video interview for MIT 150 Infinite History Project, available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYit5qV6Tww.

Chomsky, N. 2012. The Science of Language: Interviews with James McGilvray. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. 2013a. ‘After 60+ years of generative grammar’, available at: www.youtube.com/ watch?v=Rgd8BnZ2-iw (accessed 9 April 2016).

Chomsky, N. 2015. ‘Noam Chomsky and Subrata Ghoshroy: From the Cold War to the Climate Crisis’, MIT Video, available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7tVG3sRcuU4.

Chomsky, N. 2016b. ‘Language, creativity and the limits of understanding’, lecture at the University of Rochester, New York, 21 April, available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=XNSxj0TVeJs.

Chomsky, N. and C.P. Otero. 2003. Chomsky on Democracy and Education. New York: Routledge Falmer.

Dean, M. 2003. Chomsky: A Beginner’s Guide. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Edgley, A. 2000. The Social and Political Thought of Noam Chomsky. London and New York: Routledge.

Edwards, P. 1996. The Closed World: Computers and the politics of discourse in cold war America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Eun-jung, S. 2015. Verita$: Harvard’s Hidden History. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Forman, P. 1987. ‘Behind quantum electronics: National security as basis for physical research 1940–1960’, Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences, 18(1): 156–157.

Goldsmith (eds), Ideology and Linguistic Theory: Noam Chomsky and the deep structure debates. London: Routledge.

Golumbia, D. 2009. The Cultural Logic of Computation. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harman, G. (ed.). 1974. On Noam Chomsky: Critical essays. Modern Studies in Philosophy. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Harris, F. and J. Harris. 1974. ‘The development of the linguistics program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’, 50 years of Linguistics at MIT: A scientific reunion, 9–11 December 2011, MIT, available at: http://ling50.mit.edu/harris-development.

Harris, R.A. 1993. The Linguistics Wars. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jaggi, M. 2001. ‘Conscience of a nation’, Guardian, 20 January.

Johnson, H. 2001. Holding the Center: Memoirs of a life in higher education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Joseph, J.E. and T.J. Taylor. 1990. ‘Introduction’, in J.E. Joseph and T.J. Taylor (eds), Ideologies of Language. London and New York: Routledge.

Harris, R.A. 1998. ‘The warlike Chomsky. Review of R.F. Barsky, 1997. Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press’, Books in Canada, March.

Hughes, S. 2006. ‘Interview with Noam Chomsky, 21 April’, in Penn in Ink: Pathfinders, Swashbucklers,

Kabat-Zinn, J. 2014. Coming to Our Senses. London: Piatkus.

Katsiaficas, G. 1969. ‘A personal statement to the MIT Review Panel on Special Laboratories’, MIT Libraries Retrospective Collection.

Lakatos, I. 1970. ‘Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes’, in I. Lakatos and Leiber, J. 1975. Noam Chomsky: A philosophic overview. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Leslie, S.W. 1993. The Cold War and American Science: The military-industrial complex at MIT and Stanford. New York: Columbia University Press.

Mailer, N. 1968. The Armies of the Night. New York: New American Library.

Mehta, V. 1974. John is Easy to Please. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Milne, D. 2008. America’s Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War. New York: Hill and Wang.

Milne, S. 2009. ‘Noam Chomsky: US foreign policy is straight out of the mafia’, Guardian, 7 November.

Postal, P. 1995. ‘In conversation with John Goldsmith and Geoffrey Huck’, in J.H. Huck and J.A.

Price, D.H. 2011. Weaponizing Anthropology: Social science in service of the militarized state. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Rappaport, R.A. 1999. Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. 2003. Conversations with John Searle, ed. Gustavo Faigenbaum. Buenos Aires: LibrosEnRed.

Segel, J. (ed.). 2009. Recountings: Conversations with MIT mathematicians. Natick, MA: A.K. Peters.

Seuren, P.A.M. 2004. Chomsky’s Minimalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shalom, S.R. 1997. ‘Review of Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent, by Robert F. Barsky’, New Politics, NS

Skolnikoff, E.B. 2011. Video interview for MIT 150 Infinite History Project, available at: www.youtube. com/watch?v=J0cvFxzvz_c#t=22.

Smith, N. 1999. Chomsky: Ideas and ideals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Strazny, P. (ed.). 2013. Encyclopedia of Linguistics. London: Routledge.

Trask, R.L. 1999. Key Concepts in Language and Linguistics. London and New York: Routledge.

Wallerstein, I. and P. Starr (eds). 1972. ‘Confrontation and counterattack’, in I. Wallerstein and P. Starr (eds), The University Crisis Reader. New York: Random House.

White, G.D. 2000. Campus Inc.: Corporate power in the ivory tower. New York: Prometheus Books.

Wiesner, J. 2003. Jerry Wiesner: Scientist, statesman, humanist: memories and memoirs. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Williamson, J. 2004. ‘Chomsky, language, World War II, and me’, in P. Collier and D. Horowitz (eds), The Anti-Chomsky Reader. San Francisco, CA: Encounter.

Wolpert, L. 2006. Six Impossible Things before Breakfast: The evolutionary origins of belief. London: Faber & Faber.