September 19, 2019 by Matthew Reisz

[See the original version at THES website HERE]

Now 90 years old, Noam Chomsky remains one of the best-known intellectuals and critics of American foreign policy in the world. One of his first major interventions, from the time of the Vietnam War, was his celebrated essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals”. At least for those sympathetic to his politics, it remains a classic statement of the case for academics and others to speak truth to power and to resist the ever-present pressures and temptations of being co-opted. The essay formed the subject of a conference at UCL marking its 50th anniversary in 2017, at which activists and academics explored what we can still learn from it as well as where it needs rethinking.

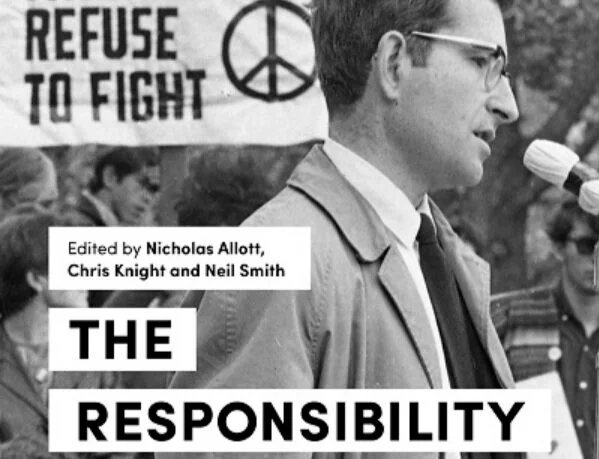

The results have now been published in a collection, edited by Nicholas Allott, Chris Knight and Neil Smith, The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and Others after 50 Years, which is available for sale but can also be downloaded for free from UCL Press. Chomsky’s broad position is well known, but he remains reliably provocative. Asked over a video link to the conference about the boycott, divestment and sanctions campaign against Israel, for example, he expressed support for “efforts to block all military aid to Israel” but pointed to “a strong and obvious taint of hypocrisy” in plans for academic boycotts: “If we’re boycotting Tel Aviv University, why not boycott Harvard and Oxford, let’s say, which are involved in much more serious crime?”

The issue of universities’ relationship with power is also central to a ferocious intellectual dispute at the heart of the book. The contribution by co-editor Chris Knight, a research fellow in anthropology at UCL, reflects on why “many people – including myself – find [Chomsky’s] political contributions so inspiring”. Since Chomsky made his career from 1955 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Knight goes on, he was working “within the belly of the beast” and “as both an insider and an outsider of the US military-industrial complex”. As a result, he “breaks the mould by speaking truth to power even when denouncing the activities of his own colleagues and friends”.

This may sound like praise, even if Knight also expresses reservations about Chomsky’s celebrated work in linguistics. Given all the other things going on at MIT, he argues, Chomsky had moral scruples that “impelled [him] to clarify that his work was restricted to pure science”. He therefore distanced himself from potential military involvement by producing abstract “models of language” that were unrealistic, since “completely removed from social usage, communication or any kind of technological application”.

In a savage response, Chomsky decries the “vulgar exercises of defamation” Knight has allegedly produced here and elsewhere, calling them valueless “except, perhaps, as an indication of how some intellectuals perceive their responsibility”. He would be quite able, he adds, to “detail how supportive ‘MIT’s managers’ were not only of me personally, but of the department generally, including all of us who were intensively engaged in political action, including very public resistance activities”.

Academic spats tend to be as long-lasting as they are acrimonious. Who can be surprised that Knight should go on to post a response to Chomsky’s response on his website?