My latest book, The Responsibility of Intellectuals – Reflections by Noam Chomsky and others after 50 years, will be published in September 2019. Edited jointly with two well-known Chomskyan linguists, Nicholas Allott and Neil Smith, it includes a chapter of mine, ‘Speaking Truth to Power’, and an intemperate response from Noam himself. Here is my reply:

Even at the venerable age of 90, Noam Chomsky remains the most influential left-wing intellectual alive today. Precisely because of this unparalleled influence, in both politics and science, Chomsky’s life and work deserve not only our appreciation and celebration but also our critical understanding. Consequently, in all that I have written, I have tried to avoid the extremes of hagiography on the one hand, denunciation on the other, in search of a more balanced historical account.

It is the responsibility of intellectuals to tell the truth. By this standard, Noam towers above most of his peers. But one thing he finds difficult. He just cannot and will not tell the truth about the US military’s intimate involvement with his own academic institution, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

It is unfortunate that Noam and I are still arguing about this particular issue. It is a fact that MIT has been and remains a centre of US weapons research, and Chomsky would do better to concede the point. Chomsky’s relationship to his institution’s research priorities is less easy to pin down. As I explain in my 2016 book, Decoding Chomsky, the supreme paradox of Noam Chomsky is that throughout much of his career, he has been the world’s leading anti-militarist activist while being employed in the world’s leading centre of military research.

Far from questioning Chomsky’s integrity on this score, I see his commitment to moral principle in the face of intense institutional pressure as in many respects a model for all of us who have no choice but to try to make our way in a capitalist world. After all, most of us on the left are compelled to earn a living in some corporation, institution or business not of our design, aware that our work may have anti-social implications even as we attempt to hold our heads high.

I am genuinely puzzled why Chomsky should want to claim that none of this applies to him. It surely makes no sense for him to downplay the fact that MIT has always focused heavily on war research.[1] In the early years, Chomsky would happily concede the point, as he did in 1970 when reminding a TV audience that ‘MIT is a major institution of war research’.[2]

Throughout his academic career, Chomsky has always been a principled anti-militarist operating in one of the world’s foremost centres of military research. My intention throughout has simply been to bring out the ramifications of this basic tension. On the one hand, Chomsky’s research into the nature of language was officially supposed to lead eventually to military applications. On the other hand, as I have laboriously stressed, Chomsky always had other ideas and was determined to maintain his principles no matter what was going on all around him.

With this in mind, I have tried to show how Chomsky’s original conception of language — puzzling in so many respects — makes better sense when viewed in the light of the ideological forces and institutional pressures against which it was ranged. Chomsky was surrounded by what must have seemed to him a swamp of institutional pressures, behaviourist psychological assumptions and demands for military and other practical applications of his work. I can fully understand his longing to rise above all this, focusing instead on the beauty of mathematical formulae, of previously unsuspected eternal linguistic truths. His concept of language as a natural object was not designed to fit within the messy, corrupted world of human social negotiation, personal ambition and politics. As an aspect of the natural world, it was intended to transcend such things. I can understand the attraction of a vision which sets language apart from the world, from social usage, from contested meanings and from the limitations of the physical brain and body. Chomsky’s whole project can seem inspiring precisely because it lifts us above worldly concerns.

Chomsky’s aim was to bring to light the detailed properties of Universal Grammar, the eternal and unchanging grammar of grammars. Sadly, despite his best efforts, none of his models proved workable in the end. Nowadays, many linguists have concluded that the project’s assumptions were misguided from the start. But what strikes me is the intensity of fury displayed by Chomsky towards anyone who casts doubt on his philosophical assumptions. When discussing politics, Chomsky comes over as principled and intransigent yet, at the same time, level-headed, sure-footed and compelling. Chomsky the activist speaks quietly, in a low monotone; he does not shout. But everything changes when Chomsky the linguist loses his cool. Tangle with Chomsky’s picture of language as individual, private, non-communicative and natural (as opposed to social, public, communicative and cultural) — and you can expect the kind of fireworks he displays in his response to me.

Since readers may not have the patience to work through the details of this dispute, I have opted to relegate the references and documentation to an appendix.

APPENDIX

WHO WAS JEROME WIESNER?

I can easily understand why Chomsky prefers to see the positive in those Pentagon advisors and other colleagues who so consistently supported him at MIT. I can sympathise, but that doesn’t mean that I can agree. Here as elsewhere, our task is to take full responsibilty and tell the truth.

Let me begin with Jerome Wiesner, the highly influential military scientist who, as laboratory director, provost and president, was Chomsky’s manager (in my essay I used the term ‘boss’) at MIT for over 20 years.

Professor Wiesner was an important figure in the development of US defence policy in the 1950s. One of his achievements was his 1957 contribution to the potent myth of a ‘missile gap’ which supposedly left the US lagging dangerously behind the Soviet Union. In his reply to me, Chomsky claims that ‘Wiesner’s role was so slight that he is not even mentioned in authoritative insider accounts of the missile gap.’ Reversing my point, Chomsky insists that Wiesner, in fact, urged disarmament while informing the Kennedy administration that the ‘missile gap’ between the Soviet Union and the US was a myth.[3]

Well, I find it hard to fathom why Noam wishes to portray President Kennedy’s chief science adviser in this way. It is true that, from the mid-1960s, Wiesner did urge some limited measures of disarmament. But he had previously – in his own words – ‘been working very hard on military weapons’.[4] His MIT colleague, Jerrold Zacharias, could hardly have been clearer when he described Wiesner as ‘soaked’ in military work including ‘submarine warfare, air defense, atom bombs, guerrilla warfare, civil defense, and psychological warfare.’[5]

White House cabinet meeting during the Cuba Missile Crisis in 1962. Jerome Wiesner is on the right with a pipe.

As if that wasn’t enough, Wiesner also worked on three of the most important government panels tasked with developing the country’s nuclear missile programme.[6] Rather than relying on commentators’ interpretations, I prefer to quote Wiesner himself who recalls, with evident pride, that

I helped get the United States ballistic missile program established in the face of strong opposition from the civilian and military leaders of the Air Force and Department of Defense.[7]

By 1957, Wiesner had been given the job of estimating how many intercontinental ballistic missiles [ICBMs] the Soviets could produce. It was in this context that Wiesner, in collaboration with a scientific colleague, Herbert York, made their fateful contribution to the whole idea of a ‘missile gap’. I see no reason to doubt York’s words:

I recall Jerome Wiesner and I estimating that [the Soviets] could produce 1000s of ICBM’s in the next few years and urging that the Gaither Committee [of President Eisenhower] base its conclusions and recommendations on that fact.[8]

A decade later, Wiesner himself confirmed this account in a speech during which he referred to the fiction of a ‘missile gap’ as a narrative ‘which, in fact, I helped invent’.[9] So Wiesner himself admitted that he had been a principal architect of the whole myth of a missile gap. Chomsky can make his case against me only by ignoring Wiesner’s own words.

Now, it is true that, in 1961, Wiesner finally admitted that his earlier calculations had been wrong. He also informed President Kennedy that if there was a gap at all, it worked the other way round: compared with the Soviets, the US possessed many more ICBMs. This must be what Chomsky has in mind when he describes Wiesner as a disarmament advocate who exposed the myth of the ‘missile gap’. But I cannot help mentioning that this peace-loving scientist still advised Kennedy as follows:

‘The nation’s ballistic missile program is lagging. The development of the missiles and of the associated control systems, the base construction, and missile procurement must all be accelerated.’[10]

Kennedy now authorised what Chomsky himself has described as ‘the biggest military increase in history’.[11] By this point, as I also said in my chapter, Wiesner was beginning to question the unrestrained stockpiling of nuclear weapons. But his concerns didn’t prevent him from helping to oversee Kennedy’s build-up. Nor did they prevent him from administering laboratories at MIT that were working on even more sophisticated missile systems.[12]

Chomsky’s tireless activism in opposition to the Vietnam War is well-known. At no point have I ever tried to play this down. But it is unclear to me why Chomsky should wish to portray Wiesner in such a positive light given his key initiating role in the development of what became known as the McNamara barrier.

Packed with state-of-the-art electronic sensors and anti-personnel mines, this huge barrier was designed to prevent movement between North and South Vietnam. An article in Volume 5 of the famous Pentagon Papers confirms Wiesner as a leading proponent of this barrier.[13] A further article in the same volume provides some idea of what was involved:

The fragmentation anti-personnel bombs, like the BLU/63, which breaks into dozens of jagged fragments, are larger and calculated to do far more damage than the steel ball-bearing pellets. Similarly, flechettes are tiny steel arrows with larger fins on one end which peel off the outer flesh as they enter the body, enlarge the wound, and shred the internal organs.[14]

Much of the research for the McNamara barrier was organised at an offshoot of MIT called the MITRE Corporation.[15] Despite his own involvement with MITRE, which I discuss later, Chomsky may have been unaware of the corporation’s precise role in Vietnam. But, as an editor of Volume 5 of the Pentagon Papers, he can hardly have missed the part played by Wiesner in the development of the McNamara barrier.

Given these facts, it is hard to understand why Chomsky would want to champion such a colleague.

Radar and bomb guidance developed at MIT aided the bombing of Vietnam.

WHO WAS GORDON MACDONALD?

Now let me come to one of the more surprising of Chomsky’s mirror-image reversals of reality. Gordon Macdonald was another leading scientist who played an important role in the creation of the McNamara barrier. He had worked for MIT in the 1950s and for MITRE from the 1960s. In Chomsky’s view, this ‘Vietnam War protestor’ deserves our gratitude for having been one of the first scientists to warn humanity about the dangers of global warming, setting alarm bells ringing as early as the 1970s.[16]

It is disappointing to find Chomsky describing Macdonald as a Vietnam War protestor, since the claim is so patently wrong. In fact, Chomsky seems to have misread his own source, a 2018 New York Times article. The piece does mention a protest against the Vietnam War, but Chomsky gets things upside down. The article clearly states that a group of anti-Vietnam war protestors ‘set MacDonald’s garage on fire’ in anger at the prominent scientist’s involvement with the infamous McNamara barrier across Vietnam.[17]

As for global warming, Chomsky again gets things upside down. He fails to mention that Macdonald made his initial findings about global warming while investigating ways to manipulate the weather for US military advantage in Vietnam and elsewhere. Among other ingenious projects, Macdonald investigated ways to destroy the ozone layer in order to expose enemy territory to radiation levels that would be ‘fatal to all life’.[18]

Such mistakes and omissions capture what I mean by mirror-image reversals of reality. I don’t think I need to say more.

WHO IS JOHN DEUTCH?

John Deutch is another MIT/MITRE war scientist who Chomsky is anxious to defend.[19] In his response to me, Noam rejects my description of Deutch as someone who brought biological warfare research to MIT. He alleges that in making this claim, I relied exclusively on an unreliable source: the underground student newspaper, The Thistle.[20] This is quite untrue. Simplifying again, Noam overlooks the fact that I backed up my account with additional references from MIT’s own newspaper, The Tech. Let me quote from this newspaper:

Beginning in 1980, Deutch took part in a classified Defense Science Board study on ‘chemical warfare and biological defense,’ and in 1984, Deutch chaired another DSB task force on the same subject. Deutch acknowledged that in that time period he had alerted the chairmen of the [MIT] chemistry department and applied biological sciences department to available army contracts for mycotoxin research. He said he sees nothing inappropriate with that action.

The Tech also reported:

Scientists in chemistry and the applied biological sciences at MIT received $1.6 million from the army to conduct basic research in toxins that could be used in biological warfare.[21]

In the version of my chapter that Chomsky responded to, I did mention a widely circulating claim to the effect that Deutch put pressure on junior faculty members to perform this toxins research. My reference to this claim was not inaccurate but it did little to help us understand Chomsky’s own relationship with MIT. For that reason, I dropped it from the final version. While rechecking my sources in response to Noam’s criticisms, I also realised that it would have served my argument still better to have included this quote from a 1982 edition of the journal Nature:

Two years ago, the Pentagon’s Defense Science Board, chaired by John Deutch of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, recommended a start on the production of binary [nerve gas] weapons and that the Department of Defense should prepare for a major increase in its chemical warfare programmes.[22]

I hope that makes the point about the sort of science that Deutch was involved in.

Again, the issue is Noam’s eagerness to defend his MIT colleagues, as if their research priorities were not military at all but were somehow compatible with his own anti-militarist commitments. To shed light on this puzzle, we need to take a look at Noam’s early career at both MIT and MITRE.

CHOMSKY AT MIT AND MITRE

It was in 1955 that Chomsky was recruited to work on a machine translation project at MIT by none other than Jerome Wiesner.[23] Noam claims that this project had ‘zero’ military significance. While it is true that machine translation as conceived at MIT was misconceived and could never work in that form, this was not realised at the time by Chomsky or anyone else. In a rush of enthusiasm, research into machine translation at MIT and elsewhere was heavily funded by the Pentagon for reasons of ‘national intelligence’.[24] As the director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, stated:

I should like to reaffirm the deep interest which we in the intelligence field have in the possibility of translation of Russian language materials, particularly in scientific fields, into English by machine.[25]

Chomsky suggests that the more we look at my sources, the more my case about MIT’s military interests crumbles.[26] But my prime source, here as always, is Chomsky himself:

I was in a military lab. If you take a look at my early publications, they all say something about Air Force, Navy, and so on, because I was in a military lab, the Research Lab for Electronics.[27]

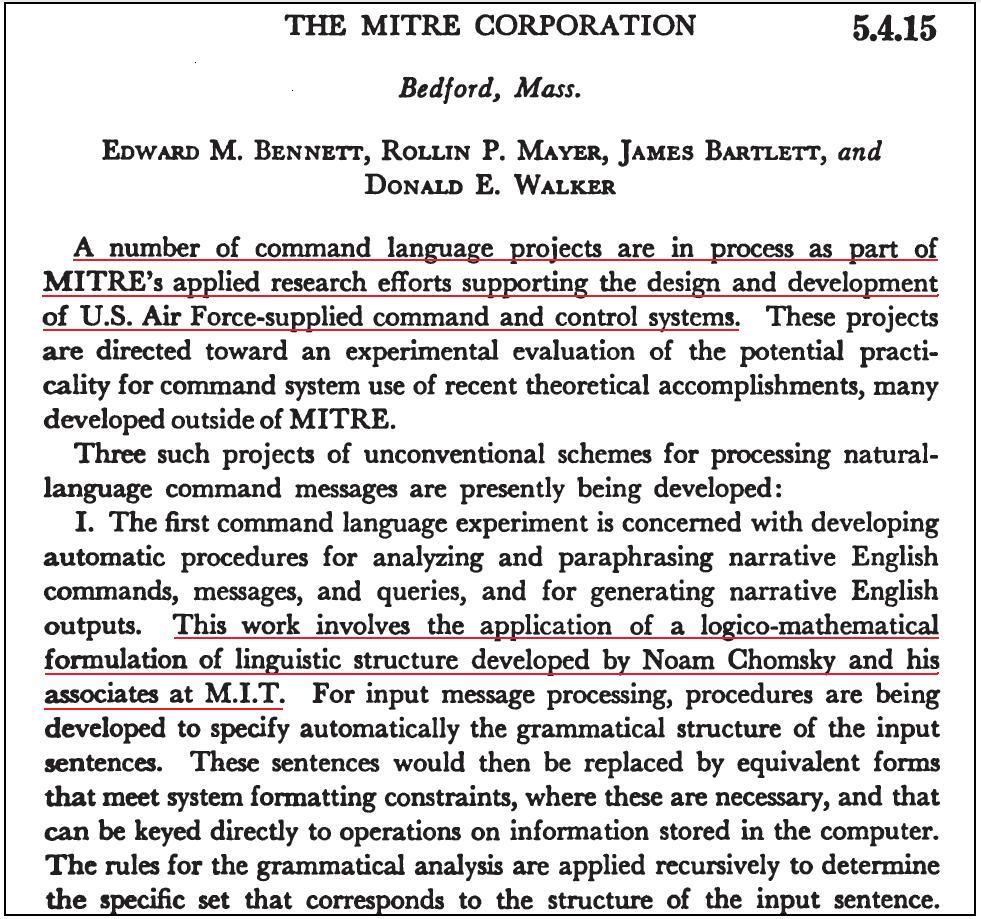

Chomsky wants us to believe that Pentagon sponsorship of his linguistics had no direct military purpose and merely reflected the fact that government funding of science had to be justified politically on ‘defense’ grounds.[28] Well, I can only say that the Pentagon themselves thought otherwise. By the 1960s, they were clearly hoping for direct military command and control applications. We have Air Force Colonel Edward Gaines’s own words to verify this:

We sponsored linguistic research in order to learn how to build command and control systems that could understand English queries directly.[29]

In 1971, the Pentagon itself stated that it made ‘a very thorough effort’ to ensure that it funded ‘only research projects directly relevant to the military’s technological needs.’ While we shouldn’t take anything the Pentagon says at face value, it is worth noting that when this particular claim was investigated by anti-militarist academics based at Stanford University, it was found to be largely accurate, even for projects from the 1960s when Pentagon science funding was especially wide-ranging.[30] These anti-militarist academics also stated, in words distinctly at odds with Chomsky’s claim, that:

The [Pentagon] purchases research to develop capabilities needed for its current and projected operational requirements, not to build a generally strong technology base for the nation. [31]

In a 2016 response to my book, Chomsky insisted that the Pentagon’s research interests ‘had nothing at all to do with our studies of universal grammar’.[32] Again, this claim is contradicted by someone who should know, former Air Force Colonel Anthony Debons:

Much of the research conducted at MIT by Chomsky and his colleagues [has] direct application to the efforts undertaken by military scientists to develop … languages for computer operations in military command and control systems.[33]

The command and control computer programs then being developed by the Pentagon were designed under the auspices of the System Development Corporation (SDC).[34] A priority for the SDC’s linguists, led by Robert Simmons, was to develop machines that could directly understand English commands, examples being ‘Blue fighter go to Boston’ or ‘Where are the fighters?’[35]

Whether they were linguists or computer programmers, Chomsky was on everyone’s lips. One historian recalls:

Linguists and programmers involved in language-based retrieval systems all around the country, including Simmons’s team at SDC, were paying close attention to Chomsky’s work and sometimes used Chomsky as a consultant.[36]

To have Chomsky as your consultant was considered the ultimate accolade. As I pointed out in the chapter which Chomsky denounces, this estimation of his significance was shared by those who recruited him to the MITRE Corporation.[37] Here is the computer scientist, Allen Newell, giving us an insight into how Chomsky was perceived at the time:

The most ambitious effort to construct an operating grammar is being made by a group at MITRE, concerned with English-like communication in command and control computer systems. It is no accident that Noam Chomsky, the major theorist in all of American linguistics, is located at MIT.[38]

From his response to me, it seems Chomsky wants us to believe that designing military command and control systems was just a side-line for MITRE, which was otherwise a non-military academic institution. If he sincerely believed this, he could never have read the recruitment adverts that appeared in 1963 in the Boston Globe, the New York Times or MIT’s own Technology Review, adverts that loudly spelled out the corporation’s real priorities:

MITRE’s principal job is the design and development of more effective military command and control systems.[39]

MITRE’s prime mission is to design, develop, and help put into operation global command and control systems that give our military commanders extra time for decision and action in case of enemy attack.[40]

MITRE’s prime mission: To design, develop and help put into operation global command and control systems for national defense.[41]

When we look at the MITRE Corporation reports that explicitly name Chomsky as a consultant – reports that he must surely have read – we find that they faithfully reflect these priorities. They clearly state that the whole point was to draw on Chomsky’s theoretical insights to develop ‘a program to establish natural language as an operational language for command and control.’[42]

By the time these documents were published in 1963, Chomsky’s boss, Jerome Wiesner, had already played an important role in helping to set up the Pentagon’s command and control systems for nuclear war.[43] He had also co-founded MIT’s linguistics department – a department that provided as many as ten trained linguists for MITRE’s command and control research.[44]

In my chapter, I describe how several of Chomsky’s students were working on linguistics for the MITRE Corporation. Among them was Jay Keyser, an officer in the Air Force whose interest was in ‘Old English Metrics’, not an obviously military topic. But we have to remember that the Air Force was explicitly interested in English, since they hoped one day to be able to use their own language when giving instructions to their computerised weapons systems. To the military, it seemed clear that Chomsky’s ideas about transformational grammar meant studying not just one form of English but a wide range of variants in order to work out the underlying grammar. If this quasi-mathematical grammar turned out to be computationally workable, then the Air Force’s computers could be programmed with this grammar. So research into Old English was entirely consistent with the dream of discovering an underlying grammar that would allow English to be used as the Air Force’s preferred control language. It was, of course, also important to study the widest variety of other languages in order to discover any underlying universal grammar which the Pentagon might find useful in the longer term.

On a rather minor point, Chomsky is quite right to point out my incorrect description of Keyser as a colonel rather than a lieutenant. I am mystified how that particular gremlin crept into a footnote in the version we sent him and I don’t blame him for making the most of it. But you only have to read Lieutenant Keyser’s 1965 report for the MITRE Corporation to appreciate why the Air Force imagined Chomsky’s insights to be relevant to their specific concerns.

Keyser may have been studying Chaucer, but from this 1965 report, you wouldn’t have known it. In the document, Keyser proposes using Chomsky’s theories for military command and control systems, illustrating his ideas with words such as ‘aircraft’ and ‘missile’ and with sample sentences such as:

The bomber the fighter attacked landed safely.[45]

In his response to me, Chomsky is silent about the actual content of Keyser’s report, just as he says nothing about the various other documents showing that the Air Force expected that his linguistic theories would indeed prove useful for weapons command and control.[46]

Perhaps the most telling of these documents is another article by Lieutenant Keyser in which he refers repeatedly to the US Air Force’s nuclear-armed bomber, the B-58.[47] Here is an extract which nicely illustrates Keyser’s sample sentences:

It is worth noting that Keyser later became head of linguistics at MIT.[48]

Perhaps still more revealing is how another researcher at MITRE, Dr. Donald Walker, justified using Chomsky’s work in his own project for the Corporation. We have the words of Barbara Partee, one of Chomsky’s students employed on this project, who explained to me in a recent email that his justification was that

… in the event of a nuclear war, the generals would be underground with some computers trying to manage things, and that it would probably be easier to teach computers to understand English than to teach the generals to program.[49]

Partee tells me she was never sure whether anyone believed this justification, but, as far as the military were concerned, something along these lines was the general idea. There can be no doubt that the whole point of the project, in the words of those leading it, was to support ‘the design and development of U.S. Air Force-supplied command and control systems.’[50]

This use of MIT’s linguistic research for ‘command language’ was only one aspect of MITRE’s wider project. Documents show that the corporation were also hoping to use MIT’s research for what they called a ‘military information system’.[51] By 1965, MITRE’s researchers claimed to have created a ‘transformational grammar’ for ‘accessing data from military planning files’.[52]

In reality, I doubt whether this transformational grammar was of much practical use considering that, as it turned out, none of Chomsky’s theories actually worked. As I have often pointed out, Chomsky simply wasn’t interested in practical applications. Neither am I trying to denigrate the work of Chomsky’s dedicated students, who were clearly fascinated by the intrinsic nature of language rather than military applications. But as the horrors of the Vietnam War became more apparent, some of these students felt uncomfortable about working for the Air Force at all. I am therefore not surprised that – as Chomsky points out – one of his students, Haj Ross, now claims that he ‘never had any whiff of military work at MITRE’ and that ‘what we talked about had nothing at all to do with command and control or Air Force.’[53] In her more nuanced account, however, Barbara Partee acknowledges the dilemmas they faced:

For a while, the Air Force was convinced that supporting pure research in generative grammar was a national priority, and we all tried to convince ourselves that taking Air Force money for such purposes was consistent with our consciences, possibly even a benign subversion of the military-industrial complex.[54]

Partee also recalls that ‘our standard rationalization was that it was better for defense spending to be diverted to linguistic research than to be used for really military purposes.’[55]

In other words, this group of young researchers genuinely wanted to believe that they were somehow tricking the Pentagon into investing in linguistics as opposed to developing weapons systems. Yet precisely who was tricking who remains an open question. After all, as long as a reasonable percentage of the research that the Pentagon sponsors ends up being militarily useful, why would the Pentagon care what their researchers thought they were doing?

Preparation for nuclear war - SAGE air defense system designed by MITRE

FREEDOM AND ‘ANARCHY’ AT MIT AND MITRE

Professor Partee also told me that she and her colleagues had ‘total freedom’ at MITRE provided their research was related to ‘topics of potential interest to the Air Force.’[56] This rather novel understanding of ‘total freedom’ is reminiscent of MITRE’s public commitment to its employees that:

At MITRE you will work closely with the Air Force, and other military organizations. You will be associated with some of America’s most important defense projects, yet you will pursue your assignments in a free and independent scientific environment.[57]

This commitment – from a 1962 MITRE recruitment advert – is itself reminiscent of General Eisenhower’s 1946 directive that military scientists ‘must be given the greatest possible freedom to carry out their research’.[58] This whole approach to military research is also consistent with what Wiesner himself termed the ‘anarchy of science’, ‘scientific anarchy’ or ‘planning for anarchy’ – all of which he saw as crucial in order to encourage the ‘free’ environment required for scientific creativity.[59]

So, it seems that creating an illusion of freedom, even anarchy, in their research facilities was always the intention of the Pentagon and its top scientists such as Wiesner. Chomsky has a remarkable gift for seeing through propaganda and official smokescreens. But in this instance, his gift seems to have failed him. Instead of exposing the deception, Chomsky has repeatedly described how genuinely free he was at MIT:

You could do what you wanted in your personal and political life, and also in your academic and professional life, within a broad range. It must’ve been one of the most free universities in the world.[60]

Well, yes. That was precisely how the Pentagon wanted its scientists to feel.

To bolster his claims about freedom, Chomsky points out that MIT’s managers were very supportive of him despite his active opposition to the Pentagon.[61] Chomsky does this to suggest that we should see these managers as genuine supporters of political, as well as intellectual, freedom. But I think it more likely that MIT’s managers followed this policy because they were not stupid. They understood perfectly that had they permitted a purge of left-leaning academics, then their entire institution – including its war work – would have been seriously undermined.[62]

To back up his arguments about political freedom, Chomsky claims that his managers created no problems ‘of any moment at MIT, for me or other activists’.[63] While this may have been true for Chomsky himself, we only have to turn to MIT’s own newspaper, The Tech, to see that when students picketed MIT’s missile laboratories or occupied its administrative offices, these managers meted out strikingly harsh punishments. In 1970, for example, they had two anti-war student activists sent to prison for the supposed crime of ‘disruption of classes’.[64] Then, in 1972, MIT took 30 activists to court for participating in an overnight occupation of military offices in the very same building as Chomsky’s own office.[65]

Twenty faculty members signed a petition in support of this particular occupation but Chomsky wasn’t one of them.[66] As he told an interviewer in 2009 while referring to the tactic of occupation: ‘I wasn’t in favor of it myself, and didn’t like those tactics.’[67]

This stance was confirmed in an interview with one of Chomsky’s MIT colleagues, Kenneth Hoffman, when he recalled an attempt in 1969 to occupy the office of MIT’s president:

See, when we were standing in the president’s office trying to protect the president’s office from the radical students, I’d look up and I’d be standing right beside Noam Chomsky.

The interviewer then intervened to say that Chomsky is ‘perceived as quite a radical himself’. Professor Hoffman replied, ‘Yes. But not if you’re going to mess around with our institution.’[68]

50 years later, Chomsky’s attitude hasn’t changed. By continuing to downplay what everyone knows about MIT’s military role, he shows once again his commitment to defending his institution.

Defending an institution like MIT was never going to be easy. When, in the late 1960s, radical students began demanding an end to war-related research at the university, Chomsky faced a serious dilemma. He didn’t want to alienate these students, but neither did he want to risk his§ academic career by fully supporting them.

Chomsky solved the problem in what seems to me to be another mirror-image reversal of reality. He redefined the students’ demand to end all war research as a right-wing position on the grounds that if MIT did comply, its war work would only be conducted somewhere else! Far better, he said, to keep it at MIT where it could be closely watched. This position, he insists, is the only genuinely ‘radical’ or ‘left-wing’ position.[69]

Accordingly, in May 1969, Chomsky signed the initial version of a report produced by the Pounds Commission, a body which had been set up in response to the growing student protests against war research at MIT. This report recommended that the university keep all its military laboratories.[70]

In October 1969, as student unrest grew stronger, Chomsky refrained from signing the final Pounds Commission report. But his proposal, in an appendix to the report – recommending that MIT’s military labs should ‘be restricted to research on systems of a purely defensive and deterrent character’ – could easily be interpreted in a way that allowed much of MIT’s war work to continue.[71]

Leaders of MIT’s anti-war students at the time, Michael Albert and Stephen Shalom, are still critical of Chomsky’s position. Shalom insists:

[We] wanted first and foremost to stop the war research … We didn’t want the war research to go on in divested labs, nor did we want it to go on in affiliated labs. We wanted the war research stopped, period.[72]

Unable to support such genuinely radical demands, Chomsky tries to persuade us that none of this mattered because, in the 1960s, the university ‘did not have war work, war-related work, on the campus.’[73] By defining war work as technically ‘off campus’, Chomsky can even make the highly misleading claim that ‘MIT itself doesn’t have war work’.[74]

The truth is that any distinction between ‘on campus’ and ‘off campus’ research was little more than a smokescreen to hide MIT’s deep military involvement.[75] As we’ve seen, the whole point of Pentagon funding for basic research ‘on campus’ at MIT was that any theoretical findings could then be developed into functional weaponry at various ‘off campus’ facilities such as the MITRE Corporation or MIT’s own Draper Laboratories.

In 1971, the Draper Laboratories – which specialised in nuclear missiles – produced a report which stated that their research facilities were still ‘an integral part of the academic structure of MIT’.[76] Further illustrating the public relations function of the ‘on campus’/’off campus’ distinction, the Pounds Commission report itself cites figures showing that as many as 500 MIT students and academics worked at the Draper and other ‘off campus’ military labs. In 1969, Chomsky himself signed this particular section of the Pounds Commission report.[77] In more recent years, Chomsky has openly admitted that MIT’s military laboratories ‘were very closely integrated with the Institute’, some being located only ‘two inches off campus’.[78]

For well over 50 years, Chomsky has fearlessly exposed and criticised every aspect of the US military machine, with one striking exception: its influence on US universities. Far from hiding or downplaying this attitude, Chomsky is on record as saying that whether a university is ‘being directly funded by the CIA or in some other fashion seems to me a marginal question.’[79] By repeatedly stressing how free he was at MIT and how distant he was from military research, Chomsky has successfully steered many commentators away from even noticing the paradoxes of his institutional position.

In his response to me, one sentence is particularly revealing. Chomsky states that his students at MITRE understood that ‘any imaginable military application [for their linguistics work] would be far in the remote future.’[80] This apparently innocuous remark is significant for two reasons. First, because it may be the nearest he has ever come to admitting that the Pentagon really did fund his linguistics in the hope of military applications. And, second, because although his students may have been reassured by the prospect of a lengthy time delay, Chomsky himself would surely not have been so easily placated.

After all, if MITRE’s linguistics research had actually succeeded, it could have led to a situation in which whenever a US commander targeted a village in a counter-insurgency operation – or targeted an entire city during a nuclear war – they would be unleashing death and destruction thanks ultimately to Chomsky’s theoretical insights. Under such circumstances, knowing that he had only developed the abstract theory, as opposed to workable applications, would have been of little comfort to someone as principled as Chomsky undoubtedly was.

So what could Chomsky do? He was too principled to come up with some convoluted argument about how war research might somehow benefit humanity. That’s the kind of argument that liberal militarists such as Wiesner would have found appealing. Chomsky preferred to keep things simple. He resolved instead, whether consciously or unconsciously, to make all his linguistic theories so utterly abstract that they stood no chance of proving useful for ‘any imaginable military application’ – not even one postponed into the ‘remote future’.

Extract from ‘Current Research and Development in Scientific Documentation’, No. 10, 1962, p. 301.

CHOMSKY’S STRANGE LINGUISTICS

In his reply to me, Chomsky denies that there is anything unusually abstract or other-worldly about his models of language. He even claims to be working in the tradition of ‘the great anthropological linguists’, Franz Boas and Edward Sapir, who did so much to advance linguistics during the early twentieth century.

This claim is so remote from the truth that we have to ask ourselves what is going on here. The idea that cultural relativists such as Boas or Sapir in any way prefigured the Chomskyan approach is jaw-dropping. These pioneering scholars considered it illegitimate to study a language without simultaneously studying the history and culture of those who spoke it. They believed there was no way to make sense of linguistic forms or associated meanings without being aware of how language was used in the speech community concerned, bearing in mind the mode of subsistence, kinship system, economic relationships, rituals, religious beliefs and so forth. Breaking with all this, it was Chomsky who did more than anyone to redefine linguistics completely, disconnecting the discipline from its former home in university cultural anthropology departments.

Chomsky is, in fact, the supreme example of a linguist whose methods relentlessly disconnect abstract theory from the realities of social and cultural life. Consistently, through all its versions and reincarnations, Chomsky’s concept of Universal Grammar disconnects the human language faculty from the rest of the brain, from speaking and listening, from context and meaning, from communicative usage of any kind, from learning and experience, and finally from culture, history, prehistory and any possible evolutionary precursor in the organic world.

In order to really understand Chomsky, we must treat him as we would any other intellectual. We must make a sustained effort to view his work in the context of his times, his community’s history and the institutional and political environment in which his ideas took shape. In his 2017 reply to me in the London Review of Books, and again in his 2019 response, Chomsky plays back this standard sociological approach of mine in unrecognizably absurd form, almost as if I were claiming a month-by-month correlation between cash receipts from the Pentagon and Chomsky’s latest idea.[81] I can agree with him that had I been distorting his motives in this way, I would deserve the accusations of ‘deceit’ and ‘defamation’ that he hurls my way.[82] Far from claiming a correlation between funds from the Pentagon and Chomsky’s latest idea, I have always argued the exact opposite – that Chomsky consistently avoided any hint of military collusion. He achieved this by disconnecting linguistic theory from linguistic practice, language from any of its possible uses and pure linguistic science from any conceivable application, whether military or not. This could only be accomplished by pursuing a level of abstraction unprecedented in the history of linguistics.

Among other details which supposedly refute my whole argument, Chomsky points out that his basic philosophical approach is not fundamentally at odds with the one he adopted while still a student. He argues that since his (in my view peculiarly abstract) approach to language pre-dated his paid employment at MIT and then remained constant throughout his life, I must be wrong to perceive any intellectual dependency on the ups and downs of Pentagon funding at MIT.

But, of course, I am not claiming any such crude dependency or correlation. My point, documented exhaustively in my 2016 book, Decoding Chomsky, is that military funding of computers and control systems was a powerful factor influencing the intellectual climate long before Chomsky got his job at MIT in 1955. It is certainly true that Chomsky was working closely with MIT’s Morris Halle on linguistic challenges from 1951, four years prior to his own appointment there.[83] 1951 was also the year when Chomsky formed a close friendship with the Israeli logician Bar-Hillel, who was in charge of all machine translation research at MIT.[84] As early as the 1940s, Chomsky’s first linguistics teacher, Zellig Harris, had already become excited by the prospect of automatic language processing, including machine translation.[85] All those in Chomsky’s circle were excited by computers in one way or another. Such was the climate of the times.

Chomsky’s ideas about language were unprecedentedly abstract from the beginning, and became increasingly so as time went on. During the early years of his academic career, Chomsky’s linguistic models were relatively rich in detail and in that sense concrete. His most fabled early work, The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, featured page after page of quasi-mathematical formulae, each item fully specified, giving the impression of a richly detailed instruction manual for computer engineers. In other early works, Chomsky was perfectly happy to analyse the sound patterning of a particular spoken language, as he did in his Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew and The Sound Pattern of English.[86]

Yet as time went on, such relatively concrete studies gave way to contributions whose most striking feature was their unprecedented generality and lack of specific content. From the standpoint of a scientist on Mars, Chomsky would eventually claim, only one language existed on Earth. Back In the late 1950s and early 1960s, most of his supporters assumed that Chomsky’s work would help them construct a transformational grammar of any language they chose to study. But these hopes were dashed when Chomsky renounced the very concept of what he termed ‘external’ languages such as spoken French or Swahili, arguing that the only scientific object of study would henceforth be ‘I-language’ – language conceived as silent and internal to the individual mind. Each locally distinctive sound pattern comprising what had previously been viewed as a speech community’s language was, from this standpoint, no more than an ‘externalization’ of something immeasurably more significant – the one language that all human beings know from birth.[87]

It seems clear to me that Chomsky’s attraction for universal and eternal truths was always driven by a felt need to rise above the messiness and temporality of language use and political life. Initially, he was prepared to go along with those of his MIT/MITRE colleagues who imagined that, one day, certain military uses might be found for a transformational grammar of, say, English or Russian. He wouldn’t actively encourage such hopes, but neither did he go out of his way to discourage them.

But then came the war in Vietnam, which revealed, as never before, the horrifying levels of death and destruction that modern armies could inflict by harnessing cutting-edge science. It was just as he was getting active on the public stage as a leading opponent of the war that he set about distancing himself from those teachers and colleagues – among them Zellig Harris – who had previously introduced him to the science of linguistics.

FROM ABSTRACTION TO ABSURDITY

If Chomsky tells me that his linguistics has no significant connection with his moral or political surroundings or ideals, I must respect his insistence on that disconnect. I am well aware that Chomsky has consistently denied any significant connection between his political activism and his science.[88] Paradoxically, however, this only strengthens my case, since my own argument rests on precisely that point.

Chomsky is faithful to a Platonic intellectual tradition in which form and content, eternal soul and mortal body, theory and practice are not required to meet up. From his earliest years right up to the present, Chomsky has always felt most comfortable with models of language so otherworldly and abstract that no one could possibly make use of them for anything at all, let alone for killing people.

This suggestion is controversial.[89] But I have come across no better way to explain some of the more incomprehensible features of Chomsky’s linguistics. Over the centuries, linguists have often adopted an abstract approach to their field. But in Chomsky, abstraction is carried to such an extreme that language is no longer connected with speaking or with social communication, history or culture at all.

According to Chomsky, when language instantaneously emerged in Homo sapiens, the result was that one mutant individual started talking to itself, not to anyone else.[90] Just as Chomsky disconnects language from any function in social communication, he routinely treats a disconnected sentence – for example ‘John is easy to please’ – as an isolated object, to be analysed apart from its conversational use. Criticising this whole approach, the influential linguist Adele Goldberg has described it as ‘akin to studying animals in separate cages in a zoo’ when they should be studied in their natural habitat. The natural habitat of language, she writes, is conversation.[91]

Chomsky also disconnects language from evolution. When asked how the biological faculty evolved, he argues that it did not. Instead he suggests that the brain of some ancestor may have been abruptly and suddenly ‘rewired, perhaps by some slight mutation’.[92] From this moment, mysteriously, the brain contained not only Universal Grammar but also specific words. Chomsky even makes the extraordinary claim that the lexical concepts we combine in sentences – examples being ‘book’, ‘bureaucrat’ and ‘carburettor’ – are genetically determined items which were installed in the mind of Homo sapiens many thousands of years before actual books, bureaucrats or carburettors had come into existence.[93]

Although Chomsky is still hugely respected as the founder of modern theoretical linguistics, the current consensus among linguists is that none of his theoretical models of Universal Grammar has survived the test of time.[94] Over the years, a number of linguists conducting fieldwork in remote corners of the world have brought to light previously unrecognized languages which bring into question Chomsky’s entire theoretical edifice. Chomsky’s response is always to retreat into a new level of generality and abstraction.

Let me illustrate with an example. In his reply to me, Chomsky invokes Kenneth Hale, the brilliant linguist employed alongside him at MIT. Hale is well known for coming up with a language which seemed inconsistent with Chomsky’s theory. Chomsky had argued that all sentences in all languages must consist of a noun phrase and a verb phrase. So these two were considered the basic ‘constituents’ of any sentence. With this in mind, the ‘constituent structure’ of a sentence depended on how these basic elements were configured, how they were arranged with respect to one another. In 1978, however, Hale told Chomsky about a language from Aboriginal Australia – Warlpiri – which violated even this most basic constraint. In this hunter-gatherer language, it seemed to make no difference whether a speaker said ‘The man speared the kangaroo’, ‘The kangaroo speared the man’ or strung the words together in any other order.[95]

Chomsky had always allowed for the fact that languages could differ from each other. But when Hale told Chomsky about Warlpiri, he was concerned that his discovery – or at least his theoretical formulation of it – made ‘languages seem more different than ought to be possible’.[96] In other words, the world’s languages now seemed far more varied than they ought to be if Chomsky’s core assumptions about constituent structure were correct.

Faced with this problem, Hale and Chomsky had to find a solution. They would make the theory of Universal Grammar (UG) so abstract that it could not possibly be wrong. On Hale’s initiative and with his support, Chomsky ruled that the presence or absence of constituent structure was just an optional ‘setting’ within the recently invented ‘principles and parameters’ model of UG. Whatever the nature of UG’s abstract principles, ran this argument, their concrete application depended on parameters which could be switched off or on.[97] Among the newly invented parameters was, Hale suggested, an on/off switch for constituent structure.[98] The beauty of this move was that, from now on, virtually anything could be declared consistent with Universal Grammar simply by inventing this or that optional parameter as required.[99] That was taking abstraction to a yet further extreme.

All this was happening during the late 1970s. Then, in the early 1990s, Chomsky retreated still further into pure abstraction with his ‘Minimalist turn’.[100] Up to this point, the idea had been that Universal Grammar imposed definite constraints because the Language Faculty was part of human nature, and this was genetically fixed. He now surmised that Universal Grammar might, after all, involve no genetic constraints at all. Chomsky suggested that the fundamental properties of language – like those of a snowflake – might instead reflect something like gravity or surface tension, a ‘natural law’.[101]

As a result of all this, one sympathetic interviewer felt bold enough to ask: ‘What exactly is UG at this stage?’ Chomsky replied: ‘Well, what’s Universal Grammar? It’s anybody’s best theory about what language is at this point. I can make my own guesses’.[102] Summing up decades of intensive work, then, Chomsky can only tell us that the nature of UG is anyone’s guess. When a theory tells you that anything goes, you really do know that this is not science.

In the eyes of most contemporary linguists, the whole concept of Universal Grammar has become so empty of content that it no longer serves any useful purpose at all. As the acclaimed psychologist and linguist Michael Tomasello remarked in 2016: ‘[Chomsky’s] universal grammar appears to have reached a final impasse’.[103]

But this still begs the question of why should any of this matter to those of us struggling to build an anti-capitalist movement in the 21st century? My answer is this. Chomsky is still the global left’s most influential living intellectual. The questions he raises are crucial ones. What does it mean to be human? What kind of creatures are we? What is the nature of language and how did it evolve?

Chomsky asks all the right questions. They are anthropological questions. But, as he disconnects mind from body and theory from practice, he inevitably sets up a stumbling block, preventing us from properly addressing such momentous and important issues. The truth is that grammar does not exist, and could not have evolved, in isolation. To understand it we must reconnect it with our social, sexual and political lives – with laughter and song, ritual and play, politics and kinship, not to mention everything else which makes us the human beings we are.

For ninety per cent of our existence as a species, we humans were nomadic hunter-gatherers, living long before private property, territorial borders, warfare or despotism had even been invented.[104] I have written elsewhere about how our bodies and minds were shaped under the egalitarian – even communistic – social conditions enjoyed by our hunter-gatherer ancestors. It was under such liberated conditions that we developed the most extraordinarily social of our genetic capacities, our ability to agree on words, construct sentences and by such means share our thoughts and dreams.[105]

Successful use of language depends on previous shared understandings, trust in communicative intentions and a willingness to hear our own words from the listener’s standpoint instead of just our own. There can be no doubt that these capacities have a genetic basis. There is such a thing as human nature and it is wired into our brains. But our capacity for language is quintessentially social, not just a device enabling us to talking silently to ourselves.[90]

Whereas Chomsky’s individualist paradigm relentlessly excludes social functions and dimensions, almost every other linguist or evolutionary anthropologist would agree with me that it is our unique social intelligence which enables language to be endlessly reinvented and creatively used. It is insights like these that have led to a growing scientific interest in the kinds of political organization which best promote the flourishing of language and creative thought.[106]

To conclude, for many years Chomsky was in the paradoxical position of being a principled anti-militarist conducting his research in an electronics lab funded by the US military. I would be disappointed if my argument were ever used to imply that Chomsky was somehow guilty of trickery or double-dealing. I am saying no such thing. In a world riven by conflicts and contradictions, all of us must somehow survive while holding our heads high. Chomsky is no exception. When I suggest that his institutional position at MIT must have involved moral challenges, I am not claiming to have any special psychological insight. In fact, I am only endorsing what Chomsky himself evidently knows. Nothing can summarise my thinking more eloquently than these words from Chomsky himself:

We’re all familiar with it in our own lives. You have interests and perceived needs, and you figure out ways of dealing with them. And unless you’re a total cynic, which few people are, you construct a belief-system which justifies them. Then you believe this belief-system and set about pursuing the needs. You do it with a high moral stance and a great sense of self-justification. Everyone does this. … Very few people are capable of saying one thing and believing another, or doing something that they recognize is completely cynical and immoral. [107]

Avoiding cognitive dissonance is not easy. It means disconnecting one part of your brain from the rest. At one level, Chomsky seems to know. I think this explains his astonishing anxiety and hostility toward anyone who probes too close.[108]

NOTES

Extracts from ‘Grammars of Number Theory Some Examples’ (MITRE Corp. 1963) by Arnold Zwicky.

1. Noam also downplayed MIT’s war research when asked by the New York Times to respond to my book (Sam Tanenhaus, ‘On Being Noam Chomsky’, New York Times, 31 October 2016). For Chomsky’s other responses to my book, see: Tom Bartlett, ‘The Chomsky Puzzle’, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 25 August 2016; Sam Fenn, ‘Chomsky's Carburetor’, Cited Podcast, no. 23, 2016 (http://citedpodcast.com/23-chomskys-carburetor/); Noam Chomsky, ‘Chomsky Says’ and ‘Chomsky has the Last Say’, London Review of Books, vol.39, no.12, 15 June 2017 and no.16, 17 August 2017. Also see note 20 on page 247 of the paperback edition of Decoding Chomsky (2018) for more examples of Noam understating MIT’s involvement in military research.

2. ‘Noam Chomsky and Michel Foucault. Human Nature: Justice versus Power’ in: Arnold Davidson, Foucault and his Interlocutors, 1997, p. 144.

3. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 98.

4. Louis Smullin, ‘Jerome Bert Wiesner, 1915-1994’, National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs, vol.78, 2000, p. 9.

5. Daniel Lang, ‘Profiles, a Scientist’s Advice - 1’, New Yorker, 19 January 1963, pp. 40, 45-6.

6. Max Rosenberg, Plans and Policies for the Ballistic Missile Initial Operational Capability, 1960, pp. iii-iv, 6-7, 17, 22; David Snead, ‘Eisenhower and the Gaither Report: The Influence of a Committee of Experts on National Security Policy in the Late 1950s’, PhD thesis, University of Virginia, 1997, pp. 59-60, 79, 153, 196, 205. Wiesner’s New York Times obituary says that he ‘argued fervently for developing and manufacturing ballistic missiles.’ Eric Pace, ‘Jerome B. Wiesner, President of MIT, is Dead at 79’, New York Times, 23 October 1994.

7. Jerome Wiesner, ‘Prof. Wiesner Explains’, Chicago Tribune, 29 June 1969, p. 24.

8. Snead, ‘Eisenhower and the Gaither Report’, 1997, pp. 188-9.

9. Donald Brennan, ABM, Yes or No? 1969, p. 33. In 1958, Wiesner publicly promoted the concept of a ‘missile gap’ – if not the exact phrase – when he told a national television audience that the Soviets ‘are ahead of us in the missile field’. Snead, Eisenhower and the Gaither Report, 1997, p. 183.

10. Jerome Wiesner, Report to the President-Elect of the Ad Hoc Committee on Space, 10 January 1961 (https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/report61.html).

11. ‘Noam Chomsky interviewed by Jerry Brown’, SPIN Magazine, vol.9, no.5, August 1993.

12. Although Wiesner became quite outspoken about the dangers of new missile systems, he apparently felt no qualms about administering the technical research required for just such systems at MIT. When asked directly how he could do this, he left little room for doubt, explaining: ‘I don’t believe I should use my position in this institution to subvert a policy of the government, even if I disapprove’ (Victor McElheny, ‘For Jerome Wiesner the Past is Prologue’, Boston Globe, 7 March 1971, p. 103.)

Wiesner’s criticisms of US nuclear policy were hardly motivated by principled anti-militarism. Rather, he believed that an overemphasis on nuclear weapons distracted the US from building what he called the ‘truly effective conventional army’ required to ‘protect the oil fields’ of the Middle East (‘The Level of Might that’s Right: An interview with Jerome B. Wiesner’, Technology Review, vol.83, no.3, January 1981, pp. 59-62).

His concerns about nuclear proliferation were equally disingenuous. So, when, in the 1970s, the Shah of Iran wanted to develop nuclear weapons, Wiesner was happy to do a deal with him – a deal which Chomsky himself summed up as MIT ‘leasing’ the university’s ‘nuclear engineering department to the Shah’. Farah Stockman, ‘Iran’s Nuclear Vision Initially Glimpsed at Institute’, The Tech, vol.127, no.11, 13 March 2007; Abbas Milani, ‘The Shah’s Atomic Dreams’, Foreign Policy, 29 December 2010.

13. Gabriel Kolko, ‘The American Goals in Vietnam’ in: Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn (eds), The Pentagon Papers, Critical Essays, Vol.5, 1972, p. 12. Volume 4 of the Pentagon Papers also mentions Wiesner’s involvement with the McNamara barrier and explains that its key requirements would include ‘20 million Gravel mines per month; possibly 25 million button bomblets per month; 10,000 SADEYE-BLU-26B clusters per month.’

A 1972 article in The Tech explains that, as MIT’s provost in the 1960s, Wiesner had been the chief officer responsible for military research and that, as its president, he now signed all its military contracts. The article then goes on to say that:

In each phase of the [Vietnam] war, MIT’s contributions have become progressively more important, until now MIT-based technology dominates the air war, and in some cases makes it possible. Failure to put a stop to MIT’s work in the past has made possible the air war and social redesigning (i.e. genocide) in Indochina today.

The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Vol.4, 1972, p. 122; Wells Eddleman, ‘Commentary: MIT may be Dangerous to the World’, The Tech, vol.92, no.21, 28 April 1972, p. 5.

14. Fredric Branfman, ‘Beyond the Pentagon Papers: The Pathology of Power’ in: Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn (eds), The Pentagon Papers, Critical Essays, Vol.5, 1972, p. 303. See also: Ann Finkbeiner, The Jasons: The secret history of science’s post-war elite, 2007, pp. 65-66, 75-76; Sarah Bridger, Scientists at War: The Ethics of Cold War Weapons Research, 2015, ch.5.

15. In its section on the Vietnam War, MITRE’s official history states that, by 1967:

MITRE was devoting almost one-quarter of its total resources to the command, control, and communications systems necessary to the conduct of that conflict.

Robert Meisel and John Jacobs, MITRE: The First Twenty Years, A History of the MITRE Corporation (1958-1978), 1979, pp. 114-5.

16. Walter Munk, et al., ‘Gordon James Fraser Macdonald’, National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs, vol.84, 2004, p. 242; Meisel and Jacobs, MITRE: The First Twenty Years, 1979, p. 266.

17. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 93; Nathaniel Rich, ‘Losing Earth: The Decade We Almost Stopped Climate Change’, New York Times, 1 August 2018.

18. Gordon MacDonald, ‘How to Wreck the Environment’ in: Nigel Calder (ed.), Unless Peace Comes; A scientific forecast of new weapons, 1968, p. 182, 191; Gordon Macdonald, Oral History Interview, no.3, American Institute of Physics, 21 March 1994. Macdonald not only investigated the use of ‘weather modification’ in Vietnam but also the use of chemical and nuclear weapons in that terrible conflict. Gregg Herken, Cardinal Choices; Presidential science advisers from the atomic bomb to SDI, 1992, pp. 158-9; Macdonald, Oral History Interview, no.3, 1994.

19. ‘Nomination of John M Deutch’, Hearings before the Select Committee on Intelligence of the US Senate, 1995, p. 110; Daniel Glenn, ‘MIT research heavily dependent on defense department funding: A Crack in the Dome’, The Tech, vol.109, no.7, 28 February 1989, p. 2.

20. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 97.

21. Thomas Huang, ‘Examining John Deutch’s Pentagon connections’ and ‘ABS, Chemistry Faculty did Bio-Warfare Research’, The Tech, vol.108, no.26, 27 May 1988, pp. 2, 11. In our Responsibility of Intellectuals book, Chomsky discusses the Clinton-era military doctrine that the US should portray itself as a country that ‘may become irrational and vindictive if its vital interests are attacked’. What Noam doesn’t mention, however, is that this doctrine was developed while his MIT colleague, John Deutch, was Deputy Defense Secretary and that it is likely that Deutch had significant input into the policy. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, pp. 84-5.

22. David Dickson, ‘Chemical Warfare Protest Plans’, Nature, vol.295, 18 February 1982, p. 545.

23. Noam Chomsky, ‘Video interview for MIT 150 Infinite History Project’, 2009 (https://archive.org/details/NoamChomsky-InfiniteHistoryProject-2009/).

24. US House of Representatives, Research on Mechanical Translation, Report of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, 1960, pp. 6-7, 10-11.

25. US House of Representatives, Research on Mechanical Translation, Report of the Committee on Science and Astronautics, 1960, pp. 6-7, 10-11. By 1968, the US Air Force were mechanically translating around 100,000 words of Russian every day. Sergei Perschke, ‘Machine Translation – the second phase of development’, Endeavour, vol.27, 1968, p. 97-9. See also: Michael Gordin, ‘The Dostoevsky Machine in Georgetown: Scientific translation in the Cold War’, Annals of Science, vol.73, no.2, 2016, pp. 208-23, and Janet Nielsen, ‘Private Knowledge, Public Tensions: Theory commitment in postwar American linguistics’, PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 2010, pp. 39-42, 194, 338.

26. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, pp. 97-9.

27. ‘Afterword, Business School: An Interview with Noam Chomsky’ in: Geoffry White and Flannery Hauck (eds), Campus Inc.: Corporate power in the ivory tower, 2000, p. 445. Funding for linguistics in this military lab was certainly generous. As Chomsky’s friend and colleague, Morris Halle, said:

There was always money available. It wasn’t a question of trying to find money, it was a question of thinking of ways of spending it. (Morris Halle, ‘50 Years of Linguistics at MIT, Lecture 10’, 2011, Youtube, 7 mins, 30 seconds.)

28. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 94. Life today is dominated by computers, the Internet and other by-products of post-war military research spending. It is therefore easy to be persuaded by Noam’s argument that this spending was primarily intended to develop ‘today’s high-tech economy’. But, of course, many other technologies – such as for example, low-pollution energy sources – were never fully developed although they could have made an equally important contribution to ‘today’s high-tech economy’. One obvious reason for this discrepancy is that low-pollution energy sources have no clear military use, whereas computers, the early Internet and – for a while – Chomsky’s linguistics were considered militarily useful.

29. Frederick Newmeyer, The Politics of Linguistics , 1986, pp. 85-6.

30. These Stanford academics mostly researched military funding that originated before the 1969 Mansfield Amendment which sought to restrict such funding to projects of direct military relevance. They were particularly critical of military-funded researchers who like to think that their research ‘is not dictated by any military problem’ and who thereby ‘ignore the fact that the [Pentagon] funds their research because it contributes explicitly to solving a military problem’. These academics also quoted a top US Air Force official who insisted that:

We don’t support broad research programs … which have little direct and apparent mission applicability to the Air Force.

Stanton Glantz and Norm Albers, ‘Department of Defense R&D in the University’, Science, vol.186, no.4165, 22 November 1974, pp. 706, 710-11; Stanton Glantz, et al., DOD Sponsored Research at Stanford: Its impact on the university, Vol. 1, ‘The Perceptions: The investigator’s and the sponsor’s’, 1971, SWOPSI, p. 7.

31. Glantz and Albers, ‘Department of Defense R&D in the University’, Science, 1974, p. 707.

32. ‘Chomsky’s Carburetor’, Cited Podcast, 2016.

33. Anthony Debons, ‘Command and Control: Technology and social impact’, Advances in Computers, vol.11, 1971, p. 354.

34. Claude Baum, The System Builders: The story of SDC, 1981, pp. 53-7, 71-7; Joel Isaac and Duncan Bell (eds), Uncertain Empire: American history and the idea of the Cold War, 2012, pp. 285-6.

35. C. Baum (ed.), ‘Natural-Language Processing’, Research Directorate Report, SDC, January 1964, pp. 7-8, 91.

36. Charles Bourne and Trudi Bellardo Hahn, A History of Online Information Systems, 1963-1976, 2003, pp. 17, 20, 43. See also: C. Baum, Research and Technology Division Report for 1966, SDC, January 1967, pp. 11-14 .

37. Arnold Zwicky, ‘Grammars of Number Theory: Some Examples’, Working Paper W-6671, MITRE Corporation, 1963, Foreword, last page; Arnold Zwicky and Stephen Isard, ‘Some Aspects of Tree Theory’, Working Paper W-6674, MITRE Corporation, 1963, Foreword, last page.

38. Allen Newell, ‘The Trip Towards Flexibility: An ongoing case of interaction between the behavioral and computer sciences’ in: George Bugliarello, Bioengineering: An engineering view, 1968, p. 271.

39. ‘Putting the World on a Blackboard’, Boston Globe, 2 June, 4 August, 25 August 1963, pp. A-9 to A-10; ‘Space Command and Control System’, New York Times, 4 August 1963, p. 117.

40. ‘How Much do you Know about MITRE?’, Technology Review, vol.64, no.4, February 1962, p. 36.

41. ‘Systems Men: Contact MITRE’, Boston Globe, 10, 17 and 31 March, 1963, pp. A-9 to A-12. See also: Meisel and Jacobs, MITRE: The First Twenty Years, 1979, especially pages: xiii, 18-9, 59, 65, 114-5.

42. Zwicky, ‘Grammars of Number Theory: Some Examples’, MITRE, 1963, Foreword, last page; Zwicky and Isard, ‘Some Aspects of Tree Theory’, MITRE, 1963, Foreword, last page.

43. Rebecca Slayton, Arguments that Count: Physics, Computing and Missile Defense, 1949-2012, 2013, pp. 47, 55-6, 156; Security Resources Panel, Deterrence and Survival in the Nuclear Age [Gaither Report], 1957, pp. v, 6-10, 27-30; Jerome Wiesner, Warning and Defense in the Missile Age, 1959 (https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB43/doc2.pdf); Howard Murphy, The Early History of the MITRE Corporation: Its background, inception, and first five years, Vol.1, 1972, pp. 180-1, 199, ch.7.

44. Kathyrn O’Neill, ‘Scientific Reunion Commemorates 50 years of Linguistics at MIT’, 2011 (https://shass.mit.edu/news/news-2011-scientific-reunion-commemorates-50-years-linguistics-mit); Antonio Zampolli, et al., Current Issues in Computational Linguistics: In Honor of Don Walker, 30 June 1994, pp. xxi-xxii.

45. Samuel Jay Keyser, ‘Linguistic Theory and System Design’ in: Information System Sciences, Joseph Spiegel and Donald Walker (eds), 1965, MITRE Corporation, pp. 495-505.

46. Another of Chomsky’s colleagues who worked for MITRE was G. Hubert Matthews. It is worth noting that, in his response to me, Chomsky is keen to mention Matthew’s work on Amerindian languages while omitting to mention his involvement with MITRE. It is also worth noting that Noam’s closest colleague at MIT, Morris Halle, ran an Air Force sponsored project to develop Chomsky’s theories or ‘computer control’ – a project with apparent connections to this MITRE work. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 95; Keyser, ‘The Case for Ordinary English’, System Engineering, 1963, pp. 20-1; Current Research and Development in Scientific Documentation, No. 14, 1966, pp. 111.

47. Samuel Jay Keyser, ‘The Case for Ordinary English’, System Engineering: an intensive course for engineers and scientists, 1963, pp. 5, 13, 19-21.

48. Samuel Jay Keyser, Mens et Mania: the MIT nobody knows, p.8.

49. ‘Chomsky’s students recall their time at the MITRE Corporation’, February 2018 (http://scienceandrevolution.org/blog/2018/2/17/chomskys-students-recall-their-time-at-the-mitre-corporation).

50. Current Research and Development in Scientific Documentation, No. 10, 1962, pp. 301-2.

51. The MITRE Corporation, Research and Experimentation, 1960-1964, January 1966, p. 90.

52. Current Research and Development in Scientific Documentation, No. 14, 1966, pp. 111-2.

53. ‘Chomsky’s students recall their time at the MITRE Corporation,’ 2018.

54. Barbara Partee, ‘Reflections of a Formal Semanticist as of February 2005’ (https://people.umass.edu/partee/docs/BHP_Essay_Feb05.pdf), p. 8n.

55. ‘Chomsky’s students recall their time at the MITRE Corporation,’ 2018.

56. ‘Chomsky’s students recall their time at the MITRE Corporation,’ 2018.

Professor Jonathan King revealed the level of self-delusion of many MIT researchers in the 1980s when he told an interviewer:

There were hundreds and hundreds of physics and engineering graduate students working on these weapons. … They’re working on [what was called] the hydrodynamics of an elongated object passing through a deloop fluid at high speed. ‘Well, Isn’t that a missile?’ – ‘No, I’m just working on the basic principle; nobody works on weapons.‘

Colm Renehan, ‘Peace Activism at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1975 to 2001: A case study’, PhD thesis, Boston College, 2007, p. 247.

57. ‘Now at the MITRE Corporation’, Boston Globe, 4 November 1962, p. A-18. See also: Meisel and Jacobs, MITRE: The First Twenty Years, 1979, p. 101.

58. James Killian, Sputnik, Scientists, and Eisenhower: A memoir of the first special assistant to the President on science and technology, 1977, p. 59.

59. Daniel Kevles, The Physicists, 2013, p. 404; Jerome Wiesner, ‘Thinking Ahead with … Jerome Wiesner’, International Science and Technology, no.2, February 1962, pp. 28-33; Engineering in Biology and Medicine Training Committee, Status of Research in Biomedical Engineering, 1968, p. 69.

60. White and Hauck, ‘Afterword …’, Campus Inc.., 2000, pp. 445-6.

61. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 97.

62. MIT was always more interested in its researchers’ contributions to military science than in their political views. This was particularly evident during Senator McCarthy’s purges of the 1950s. A former MIT provost, Walter Rosenblith, recalls with some pride that when McCarthy’s envoys came to the ‘tower of war research’ that is MIT, the university’s president, James Killian, ‘showed them the door’. ‘Online Oral History Interview: Walter A. Rosenblith’, 19 July 2000, (https://libraries.mit.edu/_archives/oral-history-transcripts/rosenblith-pdf/rosenblith-session%202.pdf) pp. 20-2.

63. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 101, note 36.

64. Michael Feirtag, ‘Battering Ram III’, The Tech, vol.91, no.55, 14 December 1971, p. 8; Bruce Schwartz, ‘Kats, Bohmer, Mom Jailed’, The Tech, vol.90, no.28, 22 May 1970, p. 1.

65. Curtis Reeves, ‘19 Appeal Trespass Cases’, The Tech, vol.92, no.28, 4 August 1972, pp. 1, 13.

66. ‘A Faculty Petition in Support of the ROTC Occupation’, The Tech, vol.92, no.27, 19 May 1972, p. 3.

67. Noam Chomsky, ‘Video interview for MIT 150 Infinite History Project’, 2009 (https://archive.org/details/NoamChomsky-InfiniteHistoryProject-2009/).

68. Joel Segel, Recountings: Conversations with MIT mathematicians, 2009, pp. 206-7.

69. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, pp. 96, 115-6; Robert Barsky, Noam Chomsky, a life of dissent, 1997, p. 140.

70. Dorothy Nelkin, The University and Military Research, 1972, pp. 81-2; Eugene Skolnikoff, ‘Video Interview for MIT 150 Infinite History Project’, 2011 (https://infinitehistory.mit.edu/video/eugene-b-skolnikoff-’50-sm-’50-phd-’65).

See also: Noam Chomsky, MIT Review Panel on Special Laboratories, Final Report, October 1969, pp. 17, 31.

71. MIT Review Panel on Special Laboratories, Final Report, October 1969, pp. 37-8.

72. Stephen Shalom, ‘A Flawed Political Biography’, New Politics, vol.6(3), no.23, summer 1997. Michael Albert, has since described Noam’s position as, in effect, ‘preserving war research with modest amendments.’ Michael Albert, Remembering Tomorrow: From the politics of opposition to what we are for, 2006, p. 98.

73. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 115.

74. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 116.

75. In the 1980s, MIT justified its continuing research on nuclear and other weapons on the grounds that such research was acceptable because it wasn’t ‘operational weapons work’. As one anti-militarist campaigner said at the time:

MIT is so deeply involved in work relating to weapons systems that they have to resort to some sort of sophistry to justify it.

The same article that reported this, also reported Wiesner saying:

If you’re going to do defense research, you should do it as well as you can. At MIT we can do it very, very well.

Robert Levey, ‘MIT Role in Research and Military Questioned: Classified Work is Done at Off-Campus Labs’, Boston Globe, 7 August 1983, pp. 1, 16.

76. James Hand (ed.), MIT’s Role in Project Apollo, vol.1, October 1971, p. 5. MIT’s president in the 1980s, Paul Gray, has clearly stated that, during the 1960s, the university’s military labs were ‘an integral part of MIT’. Jerome Wiesner, Jerry Wiesner: Scientist, statesman, humanist: memories and memoirs, 2003, p. 109.

77. MIT Review Panel on Special Laboratories, 1969, pp. 59-69.

78. Chomsky, ‘Video Interview for MIT 150 Infinite History Project’, 2009; Noam Chomsky, ‘Interview with Noam Chomsky’, Works and Days, vol.26-7, 2008-9, pp. 530-34. Chomsky has continued to contradict himself on the issue of whether MIT’s military labs were integrated with the university’s academic activities. For example, in his 2019 response to me, Chomsky clearly stated that MIT’s military labs were ‘entirely separate from the academic program’. Yet in an earlier response, in 2017, he stated that there would have been no point in separating MIT’s military labs from the university because they ‘would continue their work as before, also effectively maintaining relations with academic programmes.’ Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 96; Noam Chomsky, ‘Chomsky Says’, London Review of Books, vol.39, no.12, 15 June 2017.

79. Milan Rai, Chomsky’s Politics, 1995, p. 130.

80. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 93.

81. Noam Chomsky, ‘Chomsky Says’ and ‘Chomsky has the Last Say’, London Review of Books, vol.39, no.12, 15 June 2017 and no.16, 17 August 2017; Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 91-2.

82. Allott et al., The Responsibility of Intellectuals …, 2019, p. 101, 96-9 .

83. Mark Liberman, ‘Morris Halle: an appreciation’, Annual Review of Linguistics, vol.2 no.1, January 2016, p. 8.

84. Barsky, 1997, p. 54, 81; Chris Knight, Decoding Chomsky: Science and revolutionary and politics, p. 60.

85. Chris Knight, Decoding Chomsky: Science and revolutionary and politics, p. 56.

86. Noam Chomsky, Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew (Reprint of PhD thesis, 1951), 1979; Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle, The Sound Pattern of English, 1968.

87. Noam Chomsky, ‘Language and Mind: Current Thoughts on Ancient Problems’ in Lyle Jenkins (ed.), Variation and Universals in Biolinguistics, 2004, p. 405.

88. Noam Chomsky, Language and Problems of Knowledge: The Managua Lectures, 1988, p. 2; Denis Staunton, ‘Iconoclast and radical who takes a long view‘, Irish Times, 21 January 2006.

89. For more on my approach to Chomsky’s linguistics, see the Open Democracy debate involving myself, Fritz Newmeyer, Randy Allen Harris, Wolfgang Sperlich and others HERE.

90. ‘Actually you can use language even if you are the only person in the universe with language, and in fact it would even have adaptive advantage. If one person suddenly got the language faculty, that person would have great advantages; the person could think, could articulate to itself its thoughts, could plan, could sharpen, and develop thinking as we do in inner speech, which has a big effect on our lives. Inner speech is most of speech. Almost all the use of language is to oneself. Noam Chomsky, On Nature and Language, 2000, p. 148.

91. Adele Goldberg, Explain Me This. Creativity, competition, and the partial productivity of constructions, 2019, p. 145.